|

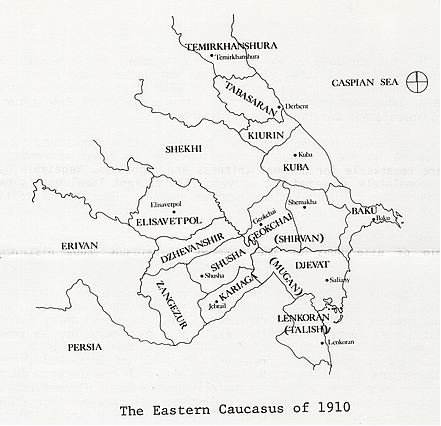

This note has to do with silk production as described in one of A. V. Piralov�s reports (A Short Sketch�.) [1]; Piralov was a long term veteran (imperial and soviet periods) of the government program in support of kustar� (home craft) enterprise, and whose primary concern was textiles.� His text reads as follows: Silk-weaving production The East once loved elaborate silk clothing and there is no doubt that in former times silk-making in various parts of Caucasia served to provide craftspeople with raw materials for the production of silk clothing, knitted goods, embroidery and galloons [narrow tightly woven ribbons].� In addition up until the 1860�s and 1870�s the production of silk for sewing was one of the major branches of the kustar� industry in the area.This sketch map may help somewhat with the place names. Silk- Producing Regions The most important silk-producing regions are, in west Caucasia, Kutaiskaya gubernia [province] and in east Caucasia, Yelisavetpolskaya gubernia, Zakatalskii okrug [distict] as well as Nakhichevanskii, Erivanskii , and Echmiadzinskii uyezd �in Erivanskaya �gubernia.� However, even in the areas listed, silk is produced only in the low-lands and foothills, where the warm climate is favorable for raising silk worms. Contemporary silk worm breeders here are trying to produce the greatest possible number of cocoons for sale to foreign exporters and local manufacturers who unwind silk to provide the raw material for major Russian manufacturers of silk cloth, primarily Moscow and Lodz [Poland]. For processing in these areas by the kustar� industry there remain only second- and third-grade �reject� cocoons: sick worms (known locally as chkhari) and doubles (dompali), as well as cocoons of the so-callled bivaliriaya variety (a Japanese variety that has degenerated in the Caucasus), which gives two harvests each summer and is not usually bought by either exporters or silk winders. In addition to the major silk; producing areas mentioned above, there is a minor amount of silk production, primarily for kustar� processing, in the Goriiskii, Sagnakhskii, Telavskii and Akhaltsykhskii uyezds in Tiflis gubernia, in the Lenkoranskii and Kubinskii uyezds of Baku gubernia, in the lowlands of Dagestan by the Caspian, in a few Kazak villages at the lower reaches of the Terek river in Terskaya oblast� and in a few isolated spots in Sukhumskii okrug and Batumskaya oblast�. The Quantity of Silk According to the Caucasus Silk-Production Station�s figures, in 1910 in Caucasia a total of 360,000 puds [13,000,000 pounds] of raw or 120,000 puds [4,300,000 pounds] of dry silk worm cocoons were harvested.� Of this amount 12,000 bales (35 kilos) or 26,468 puds, were exported through Batum to Milan and Marseilles, primarily from Kutaiskaya gubernia, while the remainder, approximately 93,500 puds, including 10,000 puds of kutaiskii cocoons, was sent to Caucasian silk winding factories to be converted into raw silk in the amount of 15-2000 puds. [2] Cocoons destined for the production of handicrafts, including those rejected by buyers, which usually comprise 7-8%, are unwound on Asian hand apparatuses.� The threads thus obtained are thick: 20-40 cocoons go into making one thread, whereas only 5-10 cocoons go into making factory-wound thread. By the end of the last century a certain amount of thread wound by the local cottage industry was being exported from Kutaiskaya gubernia to Turkey at the price of 120-150 rubles per pud, but this export has since ceased and all of the native silk that is wound goes exclusively into the kustar� production of cloth and silk thread for sewing.� According to current estimates 2,000 � 3,000 puds of this type of silk are produced in the Caucasus each year. Kustary production of silk fabrics today has lost its former significance and in what were once centers of silk weaving we now find only a relatively small number of craftspeople who carry on the traditions of the past. Silk Articles Produced by the Cottage Industry By the middle of the last century Shirvanskaya khanate, now Shemanskii uyezd, was famous for its patterned darayas and kalagayas (silk scarves with printed designs, silk coverlets, dzhedzhims, and occasionally rugs as well, was developed in Karabakh (Yelizavetpolskaya gubernia), especially in the village of Liambaran, while the town of Yelizavetpol (Gyandzha) provided the market with a large quantity of kalagayas.� To give an idea of what the silk articles of this area are like, we include two photographs of silk dzhedzhims: one from Shemanskakhinskii uyezd and the other from Shushinskii uyezd.� [Not reproduced here. �The images below are three bags photographed in the Baku carpet museum in the late 1980�s, and a 1912 color photograph of three silk articles from Shusha.� Presence of the bags in Baku suggests but does not confirm an eastern Azerbaijan origin.] The other Transcaucasian area noteworthy for the quantity of silk fabrics it produces is Georgia, especially its western part (Imeretiya), where even now silk-weaving plays a part in the economic lives of local kustary.� In Georgia a significant amount of plain white tafta or daraya was produced from raw silk, mainly for house linens. Weavers in Guriya (Ozurgetskii uyezd) produced a small quantity of colorful silk sashes, a required part of the unique costume of the Gurlytsy and Adzhartsy, as well as a striped colored, closely woven material modeled after the Turkish. The production of partly silk fabrics (silk with wool) was also important, both in Georgia and the eastern provinces of Transcaucasia as well.� And these sorts of articles are still popular today among the natives of the region, especially Muslims. Silk for sewing and embroidery, sometimes dyed various colors, is produced for domestic needs in every silk-growing area of Caucasia. Other activities related to silk-growing have survived to the present, although to a lesser extent than was once true: a) knitting and braiding in Kutaisskii, Senakski and Zugdidskii uyezds of Kutaiss gubernia, Shemakhskii gyb. and in the Mozdoskskii and Kizlyarskii sections of Terskaya oblast�; b) embroidery on cotton and velvet, chiefly in Nukhinskii uyezd of Yelizavetpolsaya gubernia; and finally, c) the production of silken cords, braid, tassels, and galloons [ribbons or braids] is found to a limited extent in silk-growing areas, especially in towns and cities. Although we lack systematic studies of the various extremely interesting branches of the silk-processing industries, we consider nevertheless that the information we have presented allows us to draw two conclusions, namely: a) in silk-growing areas there is always a sufficient quantity of raw materials for processing by the kustary in the form of second-and third-grade cocoons, and the more silk-growers increase their productivity and the more raw material they can offer to the large factories, the more of� this secondary raw material there will be; and b) among the inhabitants of these areas there is enough technical skill and even artistic training of sorts to allow the silk-processing industries to develop in conjunction with current market conditions. It seems to us that the traditional silk products of the Caucasian kustary are so interesting and original artistically and technically speaking, that their rehabilitation on a more or less broad scale cannot help but be a profitable enterprise for the kustary.� Technical and artistic guidance and cooperation in organizing the sale of these goods are certainly measures that could lead to the rebirth of these forms of Caucasian handicraft. [3] [1]Kratkii ocherk kustarnykh promyslov Kavkaza, St. Petersburg, 1913. [2]Otchet o deyatel�nosti Kavkazskoi shelkovodstvennoi stantsii za 1910 g., 1911, p.35. [3]A safe conclusion would be that silk production was widely scattered throughout the region with a number of centers of significant production.�A reasonable speculation would be that the almost immediate arrival of WW1 and ensuing disruption in Europe and in Caucasia meant that there was no rebirth.�

Copyright � Richard E. Wright, All Rights Reserved |