|

|

|

|||||||

|

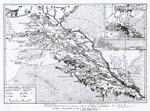

Turkmens - - Oghuz remnants -- have been in south-western Central Asia for a long time. The Khivan power sphere has long contained a significant Turkmen population, whose homeland until the 16th c. was the Mangishlak 1 peninsula (In those days the area was remote and rainfall adequate for pastoral life.) from which they were displaced by Kalmuks in the 17th c.2 and scattered up along the Amu Daria into Bukhara, and Khiva, and to the southern rim of the steppes on the mountain fringe next to Persian power. A good Turkmen ethnographic article is that by William Wood in the exhibition catalogue, Vanishing Jewels.3 He knows the Soviet sources and some European travel accounts.4 These contain data concerning Turkmens (data which are typically organized by main wings, subsidiary clans, and sometimes, families) in Khiva have predominantly to do with Yomuds and Goken, the Chodor, so to speak, bit players. Particularly instructive is a review of Khiva immediately after the Russian conquest which mentions that the Aleli moved out of the Russian sphere south into the Akhal area, 600 kibitkas (a Russian term for domicile utilized for tax purposes), which would be on the order of 3000 individuals; 7,000 kibitkas of Jemshidi moved from Khiva khanate and settled between “Kupya-Urgench in Mankytom”. The Englishman Abbott in 1840 encountered numerous Yomuds (and Jemshidi) in the Murgab valley of south central Turkmen country.5 In sum, confederation locations were fluid, changing over time, and population estimates at all times and from all sources are never reconcilable. It is the case, then, that various compilations of peoples and places other than at the most general level are a slippery plank. In addition, little is secure which connects various groupings of carpet characteristics to particular times, peoples, and places. The Khanate Khiva was an oasis town on the lower Amu Daria river (earlier, Oxus, a corruption of Turkic for White Water). The sketch map (Russian text) shows the oasis in 1850; highlights are (a) the finger lake-appearing dark areas which identify dams and water impoundments for irrigation; (b) Khiva town’s location; (c) that of Tashauz (downstream from Khiva); and, (d) the inset map which shows Turkmen areas, the diagonal lines indicating sedentary groups, the lighter lines the nomadic, and the grids of dots, those on the steppes. From the capture of Urgench (the then capital) in 1379 Khwarizm (land of Khiva) Timurid rulers were in control until 1505 or thereabouts when the mean Uzbeg Shaybani Khan drove nice Baber, last of the Timurids, into northern India. Successor Uzbeg groups ruled Khiva (Shaybanid, 1512 -- 1920) and Bukhara (Astrakhanids and Mangits, 1599 -- 1920) amid mutual conflict, ups and downs of power and territory, and buffeting by the outside: Kalmuks during the first half of the 17th century, Nadir Shah of Persia in the 1740’s, and (for Khiva) inconsequential Turkmen occupations in the first half of the 18th century.6 The Kalmuk incursions landed a large part of the Chodor confederation nearer to Khiva. The khanate power struggle ranged over most of Turkmen territory, viz. Khiva’s expeditions against Merv in 1832 and 1851.7 Tribal tribute was standard procedure; some of Khiva’s came from the ‘Ikdir-Chodor’. All of this ended when Imperial Russia expanded and imposed vassal status on Bukhara (1864) and Khiva (1872). A likeness of the then Khiva khan Seid Muhammad Rahim, complete with Russian medals, is:8 Uzbeg khans celebrated their nomad ancestry. Jenkinson (c.1550) noted the Khivan royal presence ensconced in “a little round house” replete with felts and carpets and Muraviev’ not quite 300 years later sketched the Khiva khan’s yurt serving as the reception center within the palace compound. Khiva Turkmens had been tangled up with ruling Uzbegs for centuries -- sometimes as tributary vassals, sometimes as rebels, sometimes (briefly) as victors, at others serving as agents of government, and while on the steppes pretty much independent.9 Latter-day summary reviews of source documents offer a good picture of the mixing, movement, and migration of Turkmens in and around Khiva in the 17th and mid-18th centuries, particularly those caused by Nadir Shah.10 The Chodor were one of the 22 Oghuz groups. Tamgas, tribal crests of the confederations served as signs of ownership; these were known c. 1000;11 ongons, all birds, were confederation totems. Chodor clans lived along the Amu Daria on the Bukhara Khanate’s southern border, and also were among the seven groups identified c. 1818 as living around Urgench, the old Khiva capital.12 A population estimate (c. 1840) placed the Khiva (territorially larger than subsequently) Turkmen population at 458,500 – Yomud, Tekke, Chodor, Goklan, Salor, Imrali, Aleli, Kara Daughli, Ersari, Saruk – while noting 12,000 Chodor families scattered between Khiva and the Mangishlak peninsula.13 Yomuds were present in substantial numbers (12,000 families) south of Khiva town, at least since 1760; some lived in villages but the larger part was nomadic. Although its population was predominantly Uzbeg and Turkmen, Khiva contained small groups of Armenians, Indians, Nogai, Arians, Uigurs, Kajars, Gypsies, and Negroes.14 Muraviev’ (1820) mentions the presence of 15,000 Khiva Turkmens, the majority living in villages and agricultural. The “Tchovdour-Essen-Ili” comprised 8,000 households in the Mangishlak peninsula; the principal Khiva Turkmens were Yomuds of the “Bairamcha” branch along the Caspian. Also noted were Chodor of the Igdir tribe in Mangishlak.15 Khanate archives have information describing Khiva’s multi-confederacy Turkmen population. The table below (in Russian) summarizes the ranks in descending order of importance of leaders (left axis) and lists the many clans (horizontal axis) as of the 2nd and 3rd quarter of the 19th c.16 The comparatively high total of Chodor honorifics hints at but does not necessarily reflect a large population. A travel account clan listing parallels that of the chart: Yomud, Tekke, Goklan, Salor, Imrali, Karadaghli, Ersari, Saruk.17 In the early 19th c. Khiva territory extended to the south and east into what can loosely be regarded as Tekke country, including Merv;18 an observer c. 1830 noted that the Tekke were allied with Khiva.19 By the time of these reports most Khiva Turkmens were agricultural; some were pastoral, some both. A Chodor element was located in a minor bekate, Porsu, downriver from Khiva town and around the center, Tashauz, and engaged in agriculture, giving the administration no trouble; that came from the Yomuds.20 An estimated 8000 Chodor were in Mangishlak and near Khiva c. 1810;21 a considerably later Russian census report (1886) put four thousand Yomuds there and did not mention the Chodor.22 The scholar, Bartold, writing of Khorezm when it was part of Transoxiana (before the Turkic influx), using Maqdisi as a source, noted among its exports “fabrics of striped cloth, carpets, blanket cloth”.23 A good rule of thumb is that irrespective of time periods and population changes it is safe to conclude that textiles were always a staple of intra-regional trade. In general, the small urban centers, all in irrigated oases, made sophisticated products; the rural hinterland exchanged raw materials -- sheep, camels, wool, carpet and carpet-like textiles, felts, simple stuffs, and small wares -- for items not procurable on the steppes, and always had done so, thought an anonymous traveller at the beginning of the 19th c.24 Observations about the trade of westernmost Turkmens appear regularly in the European travel literature well before the Russian conquest.25 Khiva was a mart for Turkmens: distant Tekkes sold wares there;26 carpets from “Turkomania” were imported in 1830;27 shaggy black wool hats were a Turkmen specialty; the principal (“huge”) bazaar in an outlying settlement, Kunya-Urgench, was the main Turkmen wares sales site.28 One observation concerning “Khivans” notes that “…they make fabrics of silk, of cotton, and of silk and cotton mixed together. It is the women who work these fabrics in their houses; there is no manufacturing at all in the European manner.”29 Among the goods sold to Kazaks by the oasis centers of Bukhara, Tashkent, and Khiva were “…many fabrics of silk and cotton, ‘contre-point’ robes…’30 A statement on the brink of the Russian take-over (1872) noted that Turkmen products (“coarse objects…[for] elementary needs”) from Khiva and the coastal Caspian area were exported to both Bukhara and to Persia along with livestock, salt and oil, carpets and felts.31 One summary along these lines was: “The sources, treating the beginning and middle of the 19th c., point out the following basic kinds of craft trade of the Khorezm Turkmens: carpet-making, felt boots, fabric-making (particularly fabrics and clothing from camel wool), manufacture of hats and shoes and of yurts. Crafts were of a household character, not yet drifting away from animal husbandry and farming. In my opinion, Turkmens had a small number of craftsmen specialists: blacksmiths, carpenters, builders, [although] Turkmen cattle breeders were masters at the laying out of wells. Trade transactions took place primarily through bartering for fabrics, clothing, weapons, etc. available only in the cities, as well as textile products, for Kazak livestock.”32 Another author’s list dealing with the same period identifies typical goods from the steppes including, as one would expect: herd products consisting of ewes, horses, horned beasts, camels, goats, goat hide; wool of various animals and of diverse quality; pelts of male goats, horses, sheep and cows, as well as wolves, fox, korsaks, hares and marmots, felts, dakhis (a type of clothing), touloupes (sheep pelts sewn into furs), antelope horns, and madder roots.33 According to Muraviev’ (1819) the Khiva Turkmens did not wish to live in villages and preferred a nomadic life-style (together with some steppes agriculture in patches of arable land albeit inadequate water) but nevertheless were (1) users of irrigation canals and tenders of fruit orchards, (2) owners of herds of cattle, and (3) weavers for commerce of a “considerable number” of saddle bags and of rugs and felts. Khiva town had a brisk trade with nomadic Turkmens in “couvertures”, felt and horses “remarkable for their beauty” brought up from the Gurgan/Atrek area.34 It is dangerous to read between the lines, but Muraviev’s word choice indicates that “Khivans” (likely for the most part Uzbegs) made various fabrics and other materials (city stuffs) via home industry (no workshops); and that Turkmens made humbler objects (country stuffs) -- carpets, felts.35 History has drawn a veil around late 19th and early 20th c. carpet production in Khiva, in that the Empire allowed it nominal autonomy, thereby eliminating the standard Imperial provincial bureaucracy. No annual reports describe Khivan craft activities. Data from abutting provinces, however, provide a clue concerning its carpet-making. The chart below replicates a typical provincial report. The carpet and related items production data across the years 1892 – 1911 are standard for these districts; other surveys echo them.36 These reports are economic in nature and do not get into appearances descriptions but are useful in documenting matters such as the introduction of aniline dyes (1892) and the deterioration of quality workmanship (1900). One mention, however, has to do with the Yomud women of “Karakalin” uezd (subdistrict) who made “important” palas (kilims) with fine designs on a dark ground, and prayer carpets in “beautiful and fine designs” which used cotton for pattern white, and were sold in Khiva.37 Pile rug makers in Mangishlak with its Kazak majority were Turkmens; population data compiled in 1888 states 36 thousand Kazak and 4 thousand Yomud.38 Khiva did, however, participate in the empire’s domestic craft promotion activities, one of its mechanisms being expositions; the photograph39 below is of the Khiva pavilion in Tashkent in 1890. Chodor bags form the valence along the front. The Imperial and the Soviet Carpet Literature Early 20th c. Russian publications are the principal source material. Three authors, all of whom were in the region after the turn of the century -- Dudin, Semenov, Felkersham -- form the base of knowledge about turn of the century Turkmen weaving, although they have limitations. All were experienced (one a Central Asia scholar, another an artist accompanying survey teams in the new colonial realm, and a governor-general who collected carpets) but nonetheless outsiders. A Russian taste for Turkmen craft work had developed with the conquest. For example, one of the last lootings was that of General Madritov, who when arrested after the 1917 revolution was discovered to have 600 pounds of silver jewelry taken from Turkmen women as well as over 60 fine Turkmen carpets.40 Here is the gist of what these authors wrote touching upon Khiva and the Chodor. Semenov (1911): “Turkmens weave carpets: Yomud, Chodor, Goklen, Ersari, Abdal, Igdir, and parts of Khirgiz-Kazaks and Karakalpaks. Carpets of Khiva Yomuds are the same as [those] of the Yomuds of Transcaspia ‘oblast’ [province], the same can be said about the clans Abdal and Igdir. Chodor carpets distinguish themselves in grandeur [size], a relative lack of density of fabric (especially in new carpets; the old are flawless) and an ornamentation of almost the same character as both the carpets of the Akhal and Tejend Turkmens, with only this difference, that in main designs they have bright red places…”41 Felkersham (1914): “In general the carpet production of the Yomuds, Goklens, Chodor and others is distinguished by a high quality, although they are less thin and less shortly clipped than that of Salors and Tekkes. But … the colors in them are splendid and old carpets possess silkiness to a high degree.”42 Dudin (191743 , 192644 ): The 1917 and the 1926 articles do not discuss Chodor carpets but the excellent 1917 summary survey did illustrate a bag face. Various Soviet authors have extended this literature, the most extensive being a set of reports based on field surveys in the 1930’s and 1940’s produced under the leadership of V.G. Moshkova and posthumously published in 1970. An English translation has valuable commentary by George W. O’Bannon.45 In addition, a 1968 Askhabad journal article offers many drawings of motifs but is untranslated;46 another (also not translated) contains many drawings of standard gols but the text does not discuss Chodor output.47 A later 20th c. review (in English) largely follows Felkersham.48 Moshkova, the best Soviet period source, noted in an earlier publication (1946)49 that Yomud influence caused the rugs of minor tribes to lose their original features but went on to say that Chodor and Goklen weaving nevertheless kept a distinctive quality distinguishing it from items conventionally called Yomud.50 The “distinctive quality” is not identified. An error of some consequence appears in an English version of this article employing the phrase “the original Chodor gol”; the Russian text reads “the main Chodor gol.”51 A big difference. Significant and overlooked is a 1963 tri-lingual text52 by Turkmen academics in which, while there is no text concerning Chodor carpets, some are illustrated. Most do not have the gol called ortmen. A rug woven in 1978 in Tashauz with the gol commonly called ortmen appears; its pattern, however, is termed shirbaz. This gol is the motif in all illustrations, but only once is the pattern so named. Tashauz, a Chodor town, and its rug production are cited in the old literature. The travel and the kustar’ literatures also shed light on carpets of the Khiva Chodor. The authors were interested in other things, but from time to time dropped a descriptive word. (1892) “The Turcomans-Tchaoudors have colors more gawdy [criardes],a weave less tight [serre] and a surface less fine.”53 (1900, on Mangishlak) “typical rug patterns are rare”, plus an observation of a shift from tradition to new designs and to synthetic dyes.54 Early 20th c. deterioration also is noted in an Asgabat retrospective look of 1926: “Unfortunately over the last 1/1/2-2 decades carpet production noticeably started to weaken. A propensity became evident, on the one hand -- to a decrease of merit of its own work, and on the other hand to an uncalled for imitation of Persian and European patterns. Undoubtedly it is necessary to stop these ruinous currents … [and] loss of truly artistic beauty and patterns of Turkmen historical traditional ways.” This same review noted the continuing “…work of the Chaudor tribe in the Tashauz okrug.”55 A useful survey of Chodor pile products is Munkacsy’s HALI article. He as examined many, and grouped bags into a useful compendium of characteristics: brown or brown-purple color, differences in field pattern accent colors, Persian knot open right, ribbed back, multi-colored chevrons in skirt, and, partly cotton weft alternating with wool or plied together. Cotton could indicate (a) proximity to the source, (b) possession of enough wherewithal for its purchase, or (c) a more recent date, given the Russian drive to introduce cotton culture in Central Asia to compensate for its loss due to the American Civil War. Or all of the above. New Urgench, 31 kilometers from Khiva town, by the 1880’s was the site of the oasis’ first cotton gin processing facilities56 and this fact may tip the argument toward latter days plus some economic means, ie., sedentary folks. Tashauz itself was a cotton producing area,57 and in Khiva cotton export was “so substantial” that everyone had a “secondary” knowledge of its culture.58 Why do Chodor rugs look the way they do? There are hints as to what may have been going on: “The lovely muted red Bukhara rugs of recent times probably were the result of Ozbek taste and nomadic Turkmen weaving techniques, although we have little direct evidence of their origin.”59 This taste was indeed in evidence. At the time of the Russian conquest the Khiva khan’s hastily evacuated palace was left strewn with Turkmen rugs. A traveller during a turn of the century visit to Khiva observed in re Yomud carpets: excellent in design and color, but sometimes undercut by use of bad aniline dyes, and the best carpets were “always” bought by the khan and only second class specimens were disposed of in the bazaar.60 Before the Uzbegs were the Timurids: “The Timurid and Uzbek dynasties also patronized Persian art, literature, and historical writing.”61 The Uzbeg Shaybani Khan admired Timurid culture.62 Chinese influence, as well, penetrated via the Timurids into Persia and the Uzbeg states, remaining for a long time.63 Timurid textiles involved a royal manufactory, the use of a large number of weaving techniques and materials along with frequent replication of architectural forms. Timurid fabrics (example above) have been studied via miniature paintings. While it may not be certain that things on the floor (vide the 1470 miniature above) are carpets, felts, kilims or mosaics, the designs are clear enough. And there are surviving Timurid textile fragments with a grid of rosettes, or cartouches, which touch with blossoms at the point of contact, evocation of the Sasanian style.64 The Timurid underpinning of the successor Uzbegs’ taste is unexceptionable in that conquest of central powers by less cultured outsiders frequently entails adoption by them of the center’s culture, in part for legitimization purposes and in the Uzbeg case in part because Shaybani Khan admired Timurid art. In the time of Timur Turkmens were referred to as heathen65 and in the Uzbeg period thought of as country bumpkins.66 A Timurid/Turkmen pattern correspondence was noted long ago,67 but subsequently in rug writings blithely dismissed as “superficial.”68 But what is there to expect when country folk copy high style art other than a “superficial” resemblance? And, all-over repeat patterns were endemic to Western and Central Asian textile art. Part of the Sasanian (old Persian) repertoire; part of the Sogdian (pre-Turk) Central Asia. In brief, the design approach of a major category of Timurid textiles and of Turkmen carpets is the same: a grid of geometric motifs -- circles, octagons, hexagons -- interlaced with a second grid of smaller similar motifs. This grid also frequently contained in-filling decoration of endless knots, vines, vines with blossoms. So does the vine be-draped Tashauz rug. Similar iconography of course could have arisen from other sources or spontaneously due to the inherent nature of woven materials; adaptive copying isn’t the only possibility. In this regard, however, it is useful to remember that Turkmens always to some extent wove for a market which up until the last quarter of the 19th c. was quite local. An interesting convergence thus arises: Chodors in the small town and minor district Tashauz, the ortmen motif, and proximity to the seat of Khivan Uzbeg power. All of which is only circumstantial but nevertheless leads to a plausible speculation concerning what might be not only the principal but also the original Chodor gol. This set of circumstances also suggests that this gol – and by implication others in the Turkmen formulary -- may have been created de novo at the beginning of the modern period (1600). 1 Pinkerton’s Voyages, “Accounts of Independent Tartary”, Vol IX, p. 327 – 328. 2 Desmaisons, Petr. I., History of the Mongols and the Tatars, by Ebulgazi Baradin Khan, Khiva Khan, 1603 – 1664, from a manuscript in the Arabic museum, St. Petersburg, Philo Press reprint, Amsterdam, 1970, p. 337, p. 338. 3 Wood, William, Vanishing Jewels, Turkmen Ethnohistory, Rochester, 1990. p. 27 ff. 4 Sykes, Percy, Ten Thousand Miles in Persia, 1902, London, 1902, pp. 15 – 18; Yate, C. E., Khorasan and Sistan, Edinburg and London, 1900, p. 226. p. 280; Aucher-Eloy, Remi, ed. Jaubert, Paris, 1843, pp. 347 – 48; and others. 5 Abbott, James, Narrative of a Journey, (1840) 2nd ed., London, 1856, p. 21. 6 Grousset, Rene, trans. Naomi Walford, The Empire of the Steppes, a History of Central Asia, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, 1970, p. 421, p.486– 87, p.521. 7 Riza Quoly Khan, Relation de l’Ambassade au Kharezm, trans. Chas. Schefer, Philo Press reprint, Amsterdam, 1975, p. 78, p. 89. 8 Lansdell, Henry, Russian Central Asia, Vol. II, p. 260 9 Desmaisons, Petr. I., Histoire des Mongols et des Tatars par Aboul-Ghazi Bahadour Khan, Philo Press, Amsterdam, 1970, pp. 220 –350, variously. 10 Markov, G. E., Ocherk istorii formirovaniia severnykh Turkmen, Moscow, 1961, pp. 6 – 13; 46 –55; 60 – 63; 76 – 81; 194 – 197. 11 Mahmud al-Kashgari, ed. Dankoff and Kelly, “Compendium of the Turkic Dialects”, Sources of Oriental Languages and Literatures, 7, Turkish Sources, Part I, Harvard, 1982, pp. 40-41. 12 Mir Abdul Kerim Boukhary, Histoire de l’Asie Centrale, 1740 – 1818, trans., Chas. Schefer, Paris, 1876, p. 171, p. 184 – 185, p. 194. 13 Abbott, James, op. cit., p. 176, Vol. II p. 312; Weil, Capt., La Tourkomenie et les Tourkmenes, Paris, 1880, trans. of article in Voienny Sbornik, sept/oct, 1879, p. 40.. 14 Morier, Capt., trans. Carl Zimmerman, Memoire, London, 1840, p. 48. 15 Muraviev’, N. N., Voyage en Turkomanie et Khiva, trans. J. B. Eyries and J. Klaproth, Paris, 1923, p. 105, p. 233, p. 261. 16 Bregel’, U., Khorezmskie Turkmeny v XIX veke, Moscow, 1961, p. 125. 17 Abbott, James, op. cit., Appendix. 18 Burnes, Alexander, Travels into Bokhara, London, 1834, Vol, II, p. 382. 19 Conolly, Athur, Journey to the North of India, London, 1834, p. 37. 20 Pogorel’skii, I. V., Ocherki ekonomicheskoi i politichektoi istorii Khivinskogo Khanstva, 1873 – 1917 gg., Leningrad, 1965, p. 33/34. 21 Mir Abdul Kerim Bukary, op. cit., p. 164. 22 Sbornik geografich, topograficheskikh’i statisticheskikh’ materialov’ po Azii, Statischeskiya dannyya o Zakaspiiskoi oblast’, Vol. 29, 1888. 23 Barthold, W., Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion, Oxford Univ. Press, London, 1928, p. 235. 24 Nouvelle Description de la Kharizme ou Khwarezmie, Annales des Voyages, Vol. 4, Paris, 1809, p. 382. 25 Conolly, Arthur, op. cit., p. 165; Abbott, James, op. cit., pp. 327-28; Aucher-Eloy, Remi, Relation de Voyages en Orient (de 1830 a 1838), p. 354 ff. 26 Capus, Guillaume, A Travers le Royaume de Tamerlan, Paris, 1892, p. 381. 27 Khanikof, Nikoai V., trans. de Bode, Bokhara, London, 1845, p. 224. 28 Podgorelsky, op. cit., p. 26. 29 Annales des Voyages, ed/pub Malte-Brun, Vol 4, 1809, p. 381—82. 30 DeLevchine, Alexis, Description…des Kirghiz-Kazaks, trans. from Russian, Ferry de Pigny, Paris, 1840, p. 450. 31 Nashi soisedi v Srednei Azii, “Khiva i Turkmeniya”, St. Petersburg, 1873, p. 34. 32 Bregel’, U. E., Khorezmskie turkmeny v XIX beke, Moscow, 1961, p. 66. 33 DeLevchine, Alexis, op, cit., p. 424 34 Muraviev’, N.N., op. cit., p. 7, p. 29, p. 59, p. 98. 35 Ibid., p. 89, 90, 98. English and the French translations contain key words which are inaccurately rendered. The French text is pretty much OK; the English (apparently based on a German translation) has been considerably diddled with both in words and organization and is not reliable. 36 Turkestanskii Vedemost’ No. 16 37 Obzor Zakaspiiski krai na godu 1893, pp. 91/92. 38 Sbornik geografich, topograficheskikh’ i statisticheskikh’ materialov’ po Azii, op. cit., vol. 29. 39 Courtesy of the New York Public Library 40 Pierce, Richard A., Russian Central Asia, 1867-- 1917, Cambridge University Press, London, 1960, p. 334, note 64. 41 Semenov, A., “Kovry Russkago Turkestana”, Etnograficheskoe obozrenie, No, 1 – 2, Review of the Bogoliubov book, Moscow, 1911, p. 144. 42 Felkersham, Baron, Staryie gody, Starinnye kovri Srednei Azii. October – Decermber, 1914, p. 109. 43 Dudin, S. M., Kovry Srednei Azii. Stolitsa i Usad’ba, No. 77-78, 30 Marta, 1917 g., p. 13. 44 Dudin, S. M., Sbornik muzeya antropologii i etnografii, kovrovy izdeliya Srednei Azii, Vol. VII, Moscow, 1928. 45 Moshkova, V. G., Carpets of the People of Central Asia, ed., trans., George W. O’Bannon and Ovadan K. Amanova-Olsen, 1996. 46 Saurova, G., Sovremennyi turkmenskii kover i ego traditsii, Ashkhabad, 1968. 47 Gogel, F. V., Kovry, Moscow, 1950. 48 Tsareva, Elena, Rugs and Carpets from Central Asia, Leningrad, 1984. 49 Moshkova, V. G., Kovry narodov Srednei Azii, Materialy ekspeditsii 19 – 1945 godu, Tashkent, 1970. 50 Moshkova, V. G. Carpets of Central Asia, op. cit.,p. 119, p. 177. 51 Moshkova, V. G., Sovetskaya Etnografiya, Plemennye ‘goli’ v Turkmenskikh kovrax, Moscow, 1946, p. 148. 52 Gylyzhov, A. and Klychev, A. M., Carpets and Carpet Products of Turkmenistan, Ashkabad, 1963, pp. 115 – 117. . 53 Capus, Guillaume, A Travers le Royaume de Tamerlan, Paris, 1892, p. 381. 54 Obzor zakaspiiskoy oblasti za 1900 gode, pp. 100 – 117. 55 Tumanovich, O., Materialu k izucheniu istorii i etnografii, Turkmenistan i Turkmeny, Askhabad, 1926, p. 67. 56 Podgorelski, op. cit., p. 26. 57 Tumanovich, op cit, p. 66. 58 Ivanov, P. P., Vukhiv khivinskikh khanov XIV v., Leningrad, 1940, p. 155. 59 Frye, Richard W., Bukhara, The Medieval Achievement, 1965, p. 31. 60 Olufsen, O., The Emir of Bokhara and his Country, London, 1911, pp. 230 -- 31. 61 Manz, F., ed., Central Asia in Historical Petrspective, Boulder, 1994, p. 40. 62 Allworth, Edward. A., The Modern Uzbegs, Stanford, 1990, p. 61. 63 Bouvat, Lucien, “Essai sur la Civilization Timouride”, Journal Asiatic, Apil-Juin 1926, p. 253, p. 258. . 64 Lentz, Thomas, and Lowry, Glenn, Timur and the Princely Vision, Washington, 1989, pp. 216—18. 65 Travels and Adventures of the Turkish Admiral, (1553-1556). trans. A. Vambery, London, 1899, p. 72. 66 Edward Allworth, Columbia University, in conversation. 67 Briggs, Amy, “Timurid Carpets”, Ars Islamica, Ann Arbor, 1940, p. Fig. 56, Fig. 44, p. 29. 68 Thompson, Jon, “Turkmen Carpet Weavings”, Turkmen, 1980, p. 60.

|