|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

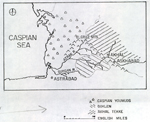

(This material may contain an occasional misspelling and one or two crossed wire references -- OK quotes but wrong source.) Several confederations lived here, principally Goklen and Yomud, along with Chodor (12,000 families) -- some in Khiva and some on the Mangishlak peninsula. [1]� �By the 19th century there also was also a consequential number of Russians in the zone using a fitting term for it, Pricaspia -- along the Caspian.� The Empire had enough at stake by 1852 to send 5,000 troops up the Gurgan watershed into the Elbruz mountains chasing Yomuds in retaliation for a raid the year before on Russian coastal outposts. Nor was Persia particularly happy with its Turkmen neighbors; a visitor to the Shah�s palace in the 1850�s remarked that between 40 and 50 Goklen families were being held there as hostages. [2] � Turkmens as Businessmen Travel accounts beginning in the early 19th c. noticed various local economic activities.� �� A trip of 1819 landed the traveller in Astrabad, on the way to Khiva but marooned for some time before he went northward; �some local observations: on the coast near the mouth of the Gurgan, grains and �numerous herds�; near the mouth of the Atrek Yomuds trading naptha from Tselekin (�naptha island�) and salt. Additional mentions included the considerable number of khurjins (saddle bags) in commerce; the making of good quality rugs; the practice of transhumance; better mannered Turkmens inland from the coast; presence of Ata and Igdir groups; �Bukhara Turkmens� in Khiva khanate not in contact with coastal bretheren; and, the sale in Khiva of carpets and felts made �on the banks� of the Gurgan and Atrek. [3] Settlements west of Astrabad traded with Turkmens for �nummuds or felts, horse clothing, carpets, packing bags called joals, salt and naptha from Balcan.� [4] Coastal zone animal husbandry was insignificant but increased with distance from the Caspian; for the most part coastal locals made simple objects for elementary needs.[5] Cotton and silk production was largely a Goklen matter, while Yomuds worked with wool, making carpets and felts decorated with �flowers� which were exported in �significant� quantities to Persia; silk stuffs, however, were also made by Imir Yomuds near �Isibli Schirvan� [6] Little economic exchange took place among Turkmens because of mutual hostility; there was �considerable� trade, however, �with Astrabad city and Khiva. [7] � Commercial activity in the 1830�s and �40�s had to do with oil, salt, fish, and horses; Ogurjalis, a Jafar Bai division on Tselekin Island, were occupied with fisheries and naptha. As for pastoralists: �The produce of their flocks, and the felts and carpets which their women make, they barter with these �jaggers� [pickers], or take across the border themselves and sell in Persia. [8] As for the island Jafar Bai, another contemporary mention added waterfowl to their commercial activity. [9] A visitor of the 1870�s summed �Pricaspiiski overland trade as consisting of slaves, horses, camels, carpets, felts and small wares, sea trade consisting of oil (125,000 pud), salt (170,000) pud, fish 450,000 pud; (a pud is about 36 pounds); fisheries were by then largely in Russian hands.[10] �In 1892 the value of export activity from Fort Alesandrov across the Caspian was -- to Astrachan, 6670 rubles; and to Baku, 1700 rubles. [11] Upshot, the littoral for the most part was settled, becoming more so as time passed.� Mangishlak Peninsula This was steppe country and therefore infrequently visited.� Kazaks -- the dominant group -- made some carpets but most were by Turkmens.� �In 1900 �all� Mangishlak wool came from the fall shearing, went entirely into kustar� work, and was sold in Ft. Alexsandrov, Khiva, and Ural Province. [12] �A visitor account from the summer of 1909 went into weaving activity in considerable detail and included some local scenery. [13] � Krasnovodosk �Area: The Goklen The once powerful but by 1821/22 �almost politically destroyed� Goklen had been driven to shelter on the southern coastal zone�s interior. [14] Astrabad (�star inhabited�), center of Kajar power (late 18th/19th c. rulers of Persia, state religion, Shiah,) was the commercial hub. � A visitor who spent four days in the early 1820�s with Goklens in the Gurgan basin noticed a lack of �the affluence and comfort� to be found among the Salors in distant Serraks. [15] Another source contains an extensive list of trade items, gathered during a lengthy stay in the 1830�s. [16]�� �The Goklans also make with cotton, a material very similar to the beze of Persia, and another striped fabric which they call sarendi�� They had �an extended commerce with Khiva and Astrabad�. �Further details on the fabrics are �� today it is toward the sources of the Gurgan, amid the homes of the Goklans, [that] this culture and the manufacture of silk are concentrated.� Silk stuffs were: katane for chemises and handkerchiefs; akatou, similar to katane; aladje or pattamber, in large pieces for loose gowns; and, meishki.� And again, Goklens were viewed as excelling in items of silk and of cotton, particularly two fabric products, one striped, and each resembling Persian and Russian cloth, Yomuds working with wool. An 1843 comment about Astrabad noted that �chools� [horse covers] and �nummuds� (felts) were sent to Teheran; Tselekin Island naptha, Balcan salt, horse covers and felts went to Astrabad in exchange for wheat, rice, sugar, manufactures.� Both Yomuds and Goklens, in the irrigated spots along the Gurgan and Atrek, grew �considerable cotton along with rice, peas, and wheat, all of which was marketed to the north to Turkmens including those in the Balkan area, and �even� to Russia. Yomuds traded with Persia; this observer held, however, that there was not much intra-Turkmen �commerce, and little with Khiva due to Tekke banditry on the steppe[17]. In sum, Goklens were agriculturalists living in a silk, not sheep, zone.� Krasnovodosk Area: The Yomuds Were the only effective military resisters to the conquest of Khiva.� An indemnity was imposed by the Russians and was paid in carpets, owners refusing to haggle; the rugs were described accurately in a very general way, noting the presence of some green. [18] Green was the Yomud favorite color for clothing (as was red for Tekkes, yellow for Saryks and Salors),� something allegedly coming from the deep past when colors were used in battle banners for identification. [19] Riza Quoly Khan put the Yomuds in the Caspian/Khiva area as of the middle of the 18th century. [20] The 19th c. western travel literature would occasionally include long lists of clans, their major divisions and sub-clans, gathered from local sources. [21] Some Yomuds were south of Khiva on the edge of dry steppes between Astrabad and the Gurgan. �Some of these � live in villages, but the largest part is nomadic.� [22] Yomuds also could be elsewhere depending on time period, as was typical for many confederations. For example, c.1840 one clan was in the Murgab watershed (well to the east), an encampment of about 300, makers of �fine carpets...almost the softness of velvet�. [23] In the late 19th c. Yomuds in Persia between the Atrek and Gurgan rivers migrated seasonally between the by then Russian zone and Persia. [24] The politics was one of Goklen-Yomud hostility. The Atabai clan was strewn along the Gurgan and the �Djafer Bay� were on the coast near Astrabad; each contained 12 groups of from 60 to 250 families. [25] An end of century visitor with the �Ak Atabai� noticed transhumanance -- five months south of the Gurgan harvesting crops, the remainder near the Atrek, grazing. Pasturage had recently been changed in order to escape taxes, 2000 families living in Russia, 1000 in Persia. �The �Jafar Bai� were involved in fisheries and on bad terms with the Atabai. [26] In 1927 the Atabai (and also the Saryks) were the only groups continuing to use traditional cattle brand markings, tagmas. [27] �(Not tamgas but serving the same function.) A more general observation at this time was that Yomuds were on Tselekin Island, and were nomadizing in the Krasnovodosk area as well as in Khiva along the Amu Daria.� The Atabai and the Jafarbai were engaged in typical coastal economic enterprises and each had units wintering between the Atrek and the Gurgan. [28] Outsiders regularly noted Yomud life styles, sometimes pastoral -- variously given as Chumur or Charwah and these were affluent, but Chawar or Chumal were settled and poor. �Varying transliterations probably have fuzzed the terms; the point is sheep = prosperity. The Imperial Period Zakaspiiski oblast� (region beyond the Caspian) had five administrative districts, two� bordering the sea. �Many Yomuds were in Khiva khanate which was nominally independent thus no Russian home industry data. � While household textiles had always been marketed locally and regionally the Russians caused a rug boom. �Horse covers were not only significant in trade but also was �culturally important.� Viz., horse furniture, as in �a very fine cover� for the husband; �indeed, a maxim was, �the more the felt cover is fine, the more the love for the horseman is grand�. [29]� Other materials were used :� ��all dressed up in silver with covering and chabraque of Khiva � less brilliant to the eye as are Bukhara trappings, but very much less costly.� [30]� In 1886 the Mangishlak and Krasnovodosk populations were 40 thousand and 15 thousand, respectively. The one, 36 thousand Kazaks and 4 thousand Turkmens, the other all Turkmen.[31]� The 1897 numbers were, for Mangishlak, 68,555, including 1,477 professional carpet-makers; and, for Krasnovodosk, 53,768 (6322 in Krasnovodosk town), including 1,864 professional carpet-makers. [32] �Felt-makers were also counted. ��There is a thumb-nail description of some Yomud felts ��variegated with red and green arabesques�. [33] The empire-wide program in support of its kustary (home artisans) began in Transcaspia in the very early 1880�s and acquired organizational structure after the turn of the century. �The furnishing of dyes and wools, the providing of training and marketing assistance, and the holding of competitive exhibitions were program elements.� Reports, some easily locatable (some not) in US libraries, [34] give a sense of product and of scale. One or two glimpses also come from outside surveys, such as the voluminous and difficult to use Palen report compiled in 1908 which expresses output in rubles and thus only roughly indicates distribution by type. [35] ����������������������������������������������������������������������������

�Smalls� (above, not Palen�s term) is a portmanteau word combining bags, tent bands, etcetera. Palen data appear elsewhere and the piece part count for the entire oblast� in 1908 was: rugs � 1750; palasi � 1240; namazlik � 738; khorjin � 1739; torbas and bags � 960.� This �report ran through the regular litany of ways in which rug quality had deteriorated but did add that silk was no longer being used. [36] � Kustar� reports do list output by type. [37]

The Mangishlak numbers are an annual average; there were no wide year to year swings.� Its home industry also made large numbers of scarves, gloves, sweaters, stockings, shawls, caftans, and fur coats.� These data can�t be totaled because of varying taxonomies used by the two jurisdictions; the problem is with the saddle bag and khorjin terms which are redundant and possibly also have gotten garbled with the torba, a smaller cousin of the chuval used for interior storage and sometimes for transport.� A general observation about the 1880�s was: �A substantial quantity of carpets, palasi, felt tents, iolani [tent bands] are produced in Krasnovodosk district, but the prices are quite high�.Carpets and palasi are exported to Persia and Khiva, where they are either sold or bartered for necessities.� Only a small proportion is exported to the Western shore of the Caspian.� Prices as follows: carpet, 5 x 3 arshin [a unit about 28 inches long] �from 60 to 100 rubles; palas the same size 35 -- 45 rubles; iolani from 12 to 15 archin 20 -- 50 rubles; iolani from 15 to 20 archin 50 -- 100 rubles; felts 3 -- 10 rubles.� Q. E. D., some of the pieces were large. A particular was noted concerning the 1880�s -- high esteem for old Yumud palasi. In 1892 Yomud women of Karakalin subdistrict were noted for quality palas with fine designs on a dark ground, and beautiful prayer carpets in various designs with cotton used for white patterning.� These were sold primarily in Khiva.� The rugs and palasi �made by Yomuds of Chekishliar sub-district were sold in Tiflis, Turkey, and France. Old palasi continued to be valued. [38] � Shifts in products also occurred, viz., in 1902: �In our times �Yomuds, Ogurjali and other tribes of Krasnovodosk uezd, which already have lost up to a certain amount of characteristic features of Turkmen drawing, acquiring a complete series of new drawings, in which it is impossible not to see borrowing and influencing by requirements of the market. � [39]� What market?� Difficult to believe it wasn�t Europe.� A big boost for exports could well have come from the exhibition of the Adarenko collection at the �Paris expo of 1900. �One might suspect the comment referenced the spread of the Salor gol, somewhat akin to an invasive species. In the Merv kustar� exhibition of December 6 and 7 of 1908 involving 80 -- 100 items a few came from Yomuds and a Yomud palas was widely admired. �Khorjin and tent bands from Karakalin pristav (smallest administrative unit) also were present. �Items which even in part had aniline dyes were excluded from prize competition no matter how skillfully made; five of the eight prize winners were made from wool and dyes obtained from the central warehouse in Merv. [40] The Pre-Revolution Literature These publications written by observers close in time and place to carpet-making are important sources although not free from error, e.g. Felkersham on the absence of tent band making in Merv, not so. �One, S. M. Dudin, an artist on some of the early 20th c. Central Asia surveys and well known as a major information source, thought rather poorly of General Bogoliubov (administrator in Askhabad), somewhat better of Baron Felkersham (traveller), and highly of Central Asian scholar Semenov, who knew the culture, got his hands on rugs on site, and noted details which were �extremely valuable�. [41] Academician Semenov (1911) [42] Reviewing the Bogoliubov exhibitions and publication of 1908, remarked (a) that Kazaks in Mangishlak district were not involved in rug making and that in Krasnovodosk the weavers were Ogurjali, Yomud, Goklen, and widely scattered Shiikh and Ata groups; (b) a negligible number of Kazaks made carpets; (c) the Yomuds of Khiva khanate and of� the province made the same type carpets, as also did the Abdal and Igdir; �(d) the motifs used by the Chodor resembled those of Akhal and Tejend; (e) a palas illustrated in the book as Plate XXI-XXII �was �especially� typical of Yomuds along the Gurgan and foreshadowed designs of Khiva� palas; (f) dyes and mordants were processed together; (g) latter day rugs with aniline dyes were made �entirely� for Europe; and, (h) the �surprisingly rich warm cherry shade� of antique carpets of Yomuds and others made with an ancient madder formula was �now almost frorgotten�; (i) sarychov (in Krasnovodsk) contained some black dye (karabaja) from a mineral mined on Chekeleten Island. � In Mangishlak the weaving clans were Khodja -- along with the Ata and Seiid of Arab descent, and by legend, the Isen�; Bogoliubov plate Table XIII is wrongly attributed to Chodor in Khiva. [43] Baron Felkersham (1914): [44] �In general the carpet production of the Yomuds, Goklens, Chodor and others is distinguished by a high quality, although usually they are less thin and clipped less short than that of Salors and Tekkes.� But on the other hand the colors in them are splendid and old carpets are silken to a high degree.� The speciality of the Yomuds is always pairs of khaliks [small rugs] and osmulduks -- carpets, reminiscent of a form of cherbak [?] made exclusively as a decoration for camels in a wedding procession; since they all set themselves apart in how they are made, otherwise in ordinary times they substitute for less short mafrash in the kibitka.� There was a considerable amount said concerning the Yomuds of the Krasnovodosk --Mangishlak border zone: �About these Yomuds, occupying pastures near Fort Aleksandrov, we have information according to the letters of M. N. Galkin from 1868; livestock raising is extremely unimportant, especially the Igdirs nomadizing from �Kinderli to Kara-Bugaz.� �The Khodzha tribes are richer� The absence of livestock raising conditions determines domestic industry, the exclusive domain of women, such as the production of carpets, etc.� The production of such is little and they almost never go into trade.� Rather originally, the design, both theirs and coastal Turkmens, without fail incorporates images of large and small anchors.� They bring dyes for carpets from Tselekin.� The trade relations of these Turkmens are limited to carpets and gunpowder with their neighbors and Yomuds living behind Kara-Bugaz.�� �The principal occupation of the Khodja tribe scattered up to about 35 miles from coastal Petrovsk appears to be the manufacture of carpets.� According to them they themselves prepare dyes and do the dyeing.� Especially surprisingly, Ivana (on the scene in 1846) advises that they, in the presence of a nomadic type of life, manage to manufacture carpets long and wide to 5 arshin [11 feet, 8 inches] and more; in truth their clipping is not always uniform.�� �Also, old white woven tent bands [iolani] with flatwoven areas and a pile pattern, per Dudin, are made by Yomuds and �kindred� groups;� previously they were in great demand for use on chair backs, and very expensive; they are not at all made in Akhal and Merv.� ��.only in the product of the Ogurjalis do the ground and ornament have equal importance.� Yomud and Ogurjali pastoralists in the same district make carpets resembling one another; with Ogurjali a �predominance of design over ground, and amount or white more or less equal to red and blue.� [45] Artist Dudin�s 1917 description [46] of Yomud carpets is: �Yomud carpets occur more rarely in commerce than Tekke.�� Larger specimens of high quality yield to several among the average Akhal carpet, but the small wares such as �enksis�, �mafrash�, �kapovs�, �asmolduks�, etc., cede not in the least to Akhal work of that kind.� The warp is grey.� The dominate shade is deep, warm madder, [in a] slightly cool shade; then the following -- black, light blue, camine-red, white, sometimes orange or yellow and blue.� Characteristics for carpets are white lines in the borders undulating with a waving out from straight line ornamentation.� The amount of white hue on the rest of surface is subordinate, as on Salor carpets. � �The middle field customarily fills out two or even one figure repeating itself -- in the appearance of stepped-rhomboids, eight sided and slanted high crosses.� Rams horns, as independent and as blended motifs, also spread out fairly often, but in recent cases -- one horn is used (but not a pair), repeating in turn on one side.� In �asmolduks� it is not a rarity to meet with figures of camels and birds.� The proportions of Yomud carpets differ from Akhals -- departing significantly beyond the square.�� Also noted are the Ogurjali whose ��carpets distinguish themselves from Yomuds slightly.� Their normal coloration is somewhat lighter.� Thanks to the fact that in the very [same] design the hue with which the background has been made is muted, they look somewhat more mottled and loud, [and] owing to that they resemble the rugs of the Transcaucasian Tatars [Azeris].� �The minor design pattern carpets of Yomud and Ogurjali nomadizing in one and the same district, for the time being it is difficult to characterize them more, since they and other carpets often resemble one another, and to determine where they come from is difficult.� With Ogurjalis it is also noticeable that usually there is predominance of the design over the ground [and] they have as a rule as much of white, as of red and blue.� Stripes, broken down, toothed, [with] rafter [?] images usually meet each other: because the designs occur abutted one to another [as] octagons, from which each divided into 4 fields or more, in which connection, in the fields special figures like the number �5� are situated�.� Some Contemporary WorkSources The one from the 1930�s (published 1970) by the Moshkova group is based on museum collections which, since production did not get underway again until 1926, implies numerous items from the pre-WWI period.� The chapter on Yomud weaving by Moshkova, Morosova, and Gavrilov covers considerable ground.[47] A 1983 publication, trilingual including English, [48] although hard to obtain is quite useful.� The authors and editors are Turkmens.� The photos are of terrible quality but the illustration index notes date (frequently vintage) and place.� Many merely indicate Krasnovodosk; however, some, such as references to Kunya-Urgench and Chekishlyar, are quite local. � A 1984 text by a Leningrad curator consists of a brief overview followed by many illustrations, a nicely representative set. [49] Lastly, detailed Turkmen carpet data have appeared in the 1980�s and 1990�s western carpet literature -- structural analysis, design grouping, and so forth, greatly advancing understanding.� Assertions concerning makers, places, and dates, however, are nebulous. The Matter of the Prayer Carpet This is a matter as puzzling as an enigma. � 1) Kustar� reports from the five administrative districts use the term prayer carpets only for Krasnovodosk. 2) Dudin noted a similarity between the enksi (sic), his stab at the Turkmen� nasal �n�, absent in the Russian alphabet, and the namazlyk -- ���very much resemble [one another] �and often they are confused but namazlik have a coarse, short fringe on the lower edge� often absent..� [50]� 3) The Tzareva book (1984) makes the briefest of mentions, and that for only the obvious Ersari Turkmen prayer rugs; this text (Ill. 103) reproduces a page from the Felkersham book which illustrates (below) an Ogurjali prayer carpet, but calls it an �Ersari horse trapping?� 4) The Turkmen authors Odjamukhavedov and Dovadov do not use the term namazlik.�� 5) Moshkova et al touch only lightly on the matter.� The O�Bannon/Amanova-Olsen translation is a bit Englishified; a more literal version is: �On account of insufficient data it is not possible to ascertain the typical decorative features of Yomud namazliks. �It seems that they were so extensively bought up and exported that they nearly disappeared from everyday use. * In the materials gathered in collections [museum holdings] in places of manufacture there is a description of only one Yomud namazlik discovered by the 1934 Expedition on Tseleken.� The bostan pattern of the Tseleken namazlik recalled the pattern of the palasi of the Karshi Arabs. ��In the upper part of the rug there is a pentagonal mihrab, distinctively patterned; the center contains a stylized representation (perhaps a bird), and the empty corner -- stylized trees and the gush dyrnak pattern.� [51] The footnoted statement concerning near disappearance is sourced to the OZO for 1912, terra incognito to these Notes. In an adjacent discussion of the engsi Moshkova matter-of-factly mentions the location of the two mihrabs typically present. An inserted reference of �Figure 2 in the O�Bannon book is to one of the many color illustrations added by that editor, is not in the original text, does not resemble the Moshkova description, and is attributed to kustar� work. [52] 6) F. Gogel reviewed the Museum of Eastern Culture�s 1927 exhibition of rugs which had been collected in 1918.� His lengthy �brochure� is what would today be called a copiously annotated self-guided tour.� One of its many details is as follows: � �Between the doors on a narrow wall is an Ogurdzhalin namazlik, a prayer rug of high production quality and dated the end of the 18th century�.. The distinctive feature of the shape of this rug consists in the fact that the contour of the upper end, which is cut along inclined lines, corresponds to the design of the recessed area�� [53] 7) The Karbala brickette (a few simple geometric shapes and an appropriate inscription) used in Shiah prayer appears as an image in the niche of prayer carpets used by Shiahs.� Some Astrabad Turkmens were Shiah. [54] What looks like such an image sometimes appears on so-called saddle covers and in engsi look-alikes. So, the prayer rug story is a convoluted one.� It would be fun to speculate about Soviet atheism and efforts to deny the Turkic republics their cultural heritage, or Russian authors, �or regional apparatchiks, or all of the above as to what if anything might have transmuted a sacred object to a secular one, but only informed speculation would be valid and that is for Central Asia experts. In Sum � As a free standing set these Coastal Turkmens notes mean nothing.� They have, however, been selected because for the most part they are place, time, object, and people specific.� Their possible role would be shedding a little light on the many pieces of the great jigsaw puzzle which is the doom and challenge for curiosity about carpet origins. [1] Abbott, James, Narrative of a Journey,2nd ed., p. 176.�� [2] Sheil, Lady Mary L. W., Life and Manners in Persia, 1856, p. 207. [3] Murav�ev, N. N., Voyage en Turkomanie et en Khiva, trans. J. B. Eyries and J. Klaproth, 1823, p. 35, P. 51, P. 59, p. 88, p. 105, p. 113.� These are correctly translated; some of the carpet notations having to do with the Khiva visit are not. Original is Puteshestye v Turkmeniu i Khivu, 1822. [4] Fraser, James B., Travels and Adventures in the Persian Provinces on the Southern Banks of the Caspian Sea, 1826, p. 15. [5]Nashi sociedi v Sredei Azii, Khiva i Turkmeniya, 1873, pp. 30--34.� [6] Archer-Eloy, Remi, Relations de Voyages en Orient (de 1830 a 1838), ed/annotated, Jaubert, VI, p. 350 ff. � [7] Spaulding, Henry, Khiva and Turkestan, 1847, p. 53, p. 61. [8] Conolly, Lt. Arthur, Journey to the North of India,1834, p. 165. [9]�Aucher-Eloy,�op. cit., p.355. [10]Nashi sociedi�, op. cit., pp. 30 � 34 [11]Obzor Zakaspiiskoi Oblasti, 1892, p. 90, p. 190. Other references to this serial by the Statistical Committee will appear simply as OZO and the year or years covered.�� [12]OZO�1892, p. 90. [13]Richard Karutz, Sredi Kirgizov' i turkmenov' na Mangishlake, 1910; also in German; Karutz, Richard, Unter Kirgisen und Turkmenen, 1911, p. 48. . [14] Fraser, James, Narrative of a Journey Into Khorassan, part 1, p. 259/260. [15]� Burnes, Arthur, Lt., Travels into Bokhara, Vol 2, 1834, p. 108. [16] Aucher-Eloy, op. cit., p. 354 ff. [17]Ibid., p. 350 ff; Fraser, Travels and Adventures .., op. cit., p. 15.� [18] MacGahan, J. A., Campaigning on the Oxus, 1874, p. 7.� [19] Karpov, G., Tagma, Turkmenovedenie #3/4, 1929, pp. 29 � 32. [20] Riza Quoly Khan, Ecole des langues oriental, 1st Series, Vol III--IV, Relation de l�Ambassade au Kharezm,trans. Chas. Schefer, p. 184. [21] Yate, Lt. Col. C.E., Khurasan and Sistan, 1900, p. 236, p. 280, 234; Sykes, Percy Molesworth, Ten Thousand Miles in Persia, London, 1902, p. 15/16. [22] Abdoul Kerim Boukhary, Histoire de l�Asie Centrale, trans. Ch. Schefer, 1876, p. 176, 180. [23] Abbott, Narrative�, op. cit., p. 17/18.� [24] Weil, Capt., La Tourkmanie et Les Tourkmenes ,trans. from Voenny Sbornik,Kuropatkin article, 1880. p. 37/38. [25] Riza Quoly Khan, op. cit. p. 58. [26] Sykes, op. cit.,p. 12--15. [27] Karpov, op. cit., p. 30. [28] Annenkova, M., Akhal-Tekinskii oazis i Puti v� Indiy, 1881, p. 7. [29] A photograph showing a flowered felt horse cover appears in the Southern Rim article in these Notes.� [30]� Moser, Henri,A Traverse l�Asie Central, 1886, p. 259. [31]Sbornik geografich, topograficheskikh� i statisticheskikh� materialov po Azii, 1888, vol 29, p. 104 ff.��� [32]Pervaya bceobshchaya perepic� naceleniya Rossiiskoi imperii, 1897 g., LXXXII. Zakaspiiskaya oblast�, 1904,1897 g. [33] Fraser, op. cit., Part IV, p. 15; Orsolle, E.,Le Caucase et La Perse, 1883, p. 361. [34]OZO, 1882-1889, 1900, 1911. [35] Palen, K. K. Count, Otchet po revizii Turkestanskogo kraya�, Materialy k kharakterisike narodnogo, khozyaistva v Turkestane, Supplement in three vol, 1911, p. 405 ff.�� [36] Yampolskii, I. P., Kustarnoye delo, Asiatiskaya Rossiya, V. II, 1914, pp. 397�400. [37]OZO�s for these years.� [38]OZO 1882 � 1890, p. 113, pp. 91/92.� [39] Dmitrieva-Mamonova, A.I.,Putevoditel� po Turkestanu, 1903, p. 116. [40]Turkestanskie Vedemost� #14, March, 1909. [41] Dudin, S.M., Kovrovye izdelii Srednei Azii, Sbornik muzeya antropologii i etnografii, T. VII, 1928, (Article written in 1926), p.75, p.103. [42] Semenov, A., Kovry Russkago Turkestana, Etnograficheskoe obzorenie, No. 1-2, 1911, pp. 108/109. [43]Ibid., p. 142. [44] Felkersham, Baron A., Starinnye kovry Srednei Azii,Starye Godu, Oct. � Dec. 1914, pp. 108/109. [45]Ibid., p. 94. [46] Dudin, S. M., Kovry Srednei Azii, Stoitza i Usad�ba, No. 77-78, 30 March ,1917g., pp. 11 -- 13. Greatly expanded in the written 1926, published 1928, article, gist unchanged.� [47] Moshkova, V. G., Carpets of the People of Central Asia, ed. and trans., George W.O�Bannon and Ovadan K. Amanova-Olsen, 1996.� [48] Odjamukhavedov, N. Dovadov, N., Carpets and Carpet Products of Turkmenistan, in English, Turkmen, and Russian, 1983. Most illustration notes are by location, and include many vintage rug types.��� [49] Tzareva, Elena, Rugs and Carpets from Central Asia,1984, pp. 104 � 133. �Warmed over Felkersham� in the view of one veteran Eastern European curator; true enough but too harsh -- the objects are, after all, the objects. [50] Dudin 1926, op. cit., p. 89, p. 127. [51] Moshkova, V. G., et al ,Kovrodelie Iomudov, Kovry narodov Srednei Azii kontsa XIX -- nachala XX vv., p. 171.�� [52] No source given for kustar� origin; it certainly wasn�t Mr. Kustar�. [53] Gogel, F.,Turkmenskii kover, 1927, p. 19. [54]Accounts of Independent Tartary, Pinkerton�s Voyages, Vol. IX, p. 329.

Copyright � Richard E. Wright, All Rights Reserved |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||