|

|

|

||||||

|

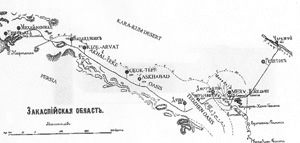

No outsider can get to bedrock with respect to Turkmen rugs. The Akhal oasis, however, may provide an opportunity for finding a few brass tacks. Although nowadays largely ignored in the lexicon, rugs of this small area were a discrete type in the pre-revolutionary Russian Turkmen carpet literature. The Embrace of the Bear Baron Felkersham correctly bounded Akhal as a 240 verst by 20—30 verst (a verst more or less equals a kilometer) strip of land flanked by Caspian Sea, desert, and mountains. 1 As such it was quite isolated, had little by way of hinterland, and was not on a trade route as was Merv. The arable land fringe immediately north of the mountains, colloquially known as the “Skirt” (Atek), was watered by rivers and streams coming down from the mountains and creating a series of oases. The Russian conquest started from a base on the Caspian and proceeded west to east through the Akhal, then peacefully to Merv, the Mervis wisely having decided not to fight. A late 1880’s map (Figure 1) shows the Skirt’s major features. The solid line running through it is the railroad; with this the isolation abruptly ended. The curving dashed line is the outer limit of Akhal oasis. Various westerners, usually English, had been in the area, but these for the most part were military reconnoiters having to do with terrain and routes, and largely uninterested in the socio-economic setting. Not all had tunnel vision. One 1839 trip noted the presence of carpets of quality as well as the sedentary agricultural population. 2 But it is Russian sources which are genuinely descriptive. To be expected, for a new colonial fiefdom was of interest. The tipping point of the Russian military operation was the defeat of the Akhal Tekke in 1881 at the fortress Geok Tepe. The advance (8,000 troops, 58 cannon) proceeded via construction of a railroad soon extended (1888) to Bukhara and Samarcand. Looting took place after the slaughter at Geok Tepe, rugs very much in evidence. An Armenian sutler with the Russian force participated in the second day of pillaging and acquired “a large number of valuable carpets”, subsequently confiscated by the authorities. 3 A later -- and likely less than accurate observation (1895) -- had the looting going on for a week with the value of things stolen as three million rubles. 4 Armenian merchants arrived on the heels of the Russians, obtaining rugs “in quantity” for resale. 5 By 1885 the Askhabad commandant, Komaroff, was collecting them. 6 Since the initial administration of the new province was based in Tiflis, some rugs found their way to Caucasia; in 1889 “Turcoman carpets from Merve” somewhat improbably were on the walls of a Daghestan khan’s home. 7 Numerous post-conflict surveys of Akhal and environs identified its peoples, places and products. 8 One written in the wake of a 1879 Russian campaign noted the pronounced degree of cultivation in the area. 9 A latter 20th century Soviet journal article sums and references most of these compilations. 10 The area was, in brief, arable, irrigated, cultivated land with a large sedentary population; both clan and family had nomadic and sedentary wings. In 1888 a traveller trekked from Kizil Arvat through extensive truck gardening and its various crops -- cucurbits, grains, animal fodder, etc. -- and a nascent silk industry, trees only recently having been planted. It was at the 130 kilometer mark that rug and palas (kilim) weaving began in earnest, activity in virtually every household, building up to a dense concentration in Merv. The point where rug making began to intensify would have been somewhat east of Geok Tepe. Also noted was that rugs here, unlike those of Persia, were made with vegetable dyes. The author went on to say that carpets “up until now [are] not in use by us” due to the absence of good roads, but because of the railroad, “will not be slow” to appear in European markets. 11 Turn-of-the-century government reports said the same, adding the facilitating role of the telegraph. One travel account is frustrating. Henri Moser went to Akhal, the only place he visited, before 1885, having crossed the desert from the north, an unusual route. While there he remarked on the “fine embroideries and beautiful rugs” of Akhal. 12 Mosher purchased some of these and returned to Switzerland. Dying in 1924, he donated his many-faceted collection of objets de virtu to the public. But not the rugs, left to his wife; there seems to be no way to trace them. A significant

consequence of one of the early Russian survey expeditions was a

recording of Akhal designs: 13 Tekke Ornamental Designs

together with their application for Carpets, Embroidery etc.

“For” is a key word. This is a straightforward book consisting

of (a) illustrations of possibilities for carpets and carpet-like

products to serve as furnishings in European settings, and (b) drawings

of motifs to serve as patterns for rugs and embroidery. The drawings, of course, are recognizable at a glance as being cartoons. These, rather than the furnishings illustrations, are what is important: a compendium of motifs then in use in Akhal. Its relative prior isolation from both Yomuds and Mervi means less outside influence, and a reasonable chance of motif fidelity to the past. The Imperial Apparatus Administration followed standard arrangements for managing a province (oblast’). One was creation of five districts (Figure 2) with Askhabad City as capital. Imperial Russia was extremely good at cataloguing. The great census of 1897 tabulates the Transcaspia population, its nature and distribution, during the vintage weaving period, 1880 – 1915. Numbers of interest are: Askhabad district, 92,205, with 19,426 in Askhabad City; Merv district, 119,255, with 8,533 in Merv City. The key data are those having to do with carpet makers: Askhabad district -- 376; Merv district -3194. 16 Normal government interest in local craft activity began promptly with a kustar’ section appearing in each provincial annual report. From about 1900, functionaires were worrying about weavers’ movement away from traditional designs. Standard kustar’ support measures slowly came into being -- promotional exhibitions (Merv, 1908, 1909, 1910; Askhabad, 1912), establishment of wool warehouses, furnishing of dyestuffs. But there were no training schools for weavers. During the period 1883 – 1889 Askhabad rug production averaged 54 per year, outputs rising toward the end. For palas the yearly average was 385, tailing off the last three years. 17 Beginning in 1900 production data appear for both Askhabad and Merv and reveal an interesting difference in scale. Statistics for 1900 show 114 rugs and 336 palas made in Askhabad, 1146 rugs and 26 palas produced in Merv. 18 Data of 1907 are for rugs only, expressed in ruble value: Askhabad 9230, Merv 83700. 19 The 1910 numbers for Askhabad were -- rugs, 310; palas, 196; for Merv, rugs, 913; palas, 75. 20 Piece counts in 1911 were: Askhabad – rugs, 208; palas 200; and, Merv – rugs, 1115; palas, 101. 21 The data underscore the point that home weaving was not only a domestic matter but also an economic activity. Immediately prior to World War I (a back-breaking blow to carpet-making) both Merv and Askhabad enterprises were hiring weavers in order to produce for the commercial market, although “European buyers” had not yet arrived . 22 Appearances: designs A 1903 travelogue treated rugs of Akhal as a distinct type. After noting the Merv penchant for use of the Salor gol the author added “…characteristic designs can most conveniently be distinguished as: Akhal, Ersari, Yomud roses, and the patterns of namazliks and ensi …” 23 In 1914 Akhal products continued as a category: “In addition to the Salir design frequently used by Tekke-craftsmen of the Merv area, there are the well known designs of the Akhal, Ersari, and Yomud types..” 24 The Akhal carpet remained distinct at least until 1930. “Tekke. A completely different type of rug. Its name is observed in literature. But in all the markets, the name of Bukhara is used to cover all the varieties of weaving techniques of the production-districts, for example: Akhal-Tekke, Merv (double-wefted) and properly Tekke.” 25 The early Russian authors quibbled over provenance assignment of particular rugs between Merv and Akhal. Semenov’s commentary on Bogolubov followed the not uncommon reviewer practice of devoting a great deal of ink to what the reviewer thought, and not so much to the book’s contents. (Semenov was a major scholar, the best of the early authors in Dudin’s opinion, Semenov having been the one who spent time in the area.) Dudin similarly had nit picks with some of both Bogolubov and Felkersham’s attributions. This discourse took place via artist illustrations and the argument was in terms of design. The Akhal design lode is the Akstaf’ev book with its 28 illustrations, all standard Turkmen motifs; four are reproduced (from some very blurry Soviet microfilm) here -- a pair of gol variants and a pair of border motif variants. One gol is somewhat round (Figure 3), another somewhat flat (Figure 4). While artist copies of motifs into cartoons may distort (possibly the secondary gols), it is difficult to think that either their shapes or the vertical and horizontal connecting lines them are embellishments. Of the two lobed leaf motifs, the one is naturalistic and curved, (Figure 5), the other (Figure 6), geometric. That both were in use at one place in the same time puts a necessary caution on Gogel’s 1927 hypothesis that this particular motif evolved from the natural to the geometric. 26 Willy-nilly any such proposition, the motifs coexisted in Akhal. In art, the new necessarily supplanting the old is scarcely an iron law, something to bear in mind with respect to the alleged flattening of the Salor gol over time. It turns out there is a fly in the Akstaf’ev ointment. Semenov, 27 noting that the motifs were rendered “with utmost accuracy”, went on to point out that some were copied from war booty carpets (Yomud and Salor) hanging on yurt walls in Akhal. It is good to find an instance of this type of rug migration, but it does mean the Akstaf’ev motifs are not all Akhal. The earlier (1917) succinct Dudin essay on Central Asian rugs deals with “Tekke or Akhal” products as a group, the better examples characterized as only “a little” inferior to those of the Salors, being on average a bit coarser. Akhal carpets are identified as being somewhat wide and squareish with the reverse side having a lighter cast than those of the Salors because the Akhal warp was made of undyed white yarn. White similarly features in the pile colors “often (to) … a rather loud effect” 28 as can be seen in the 1901 photograph of Figure 7. Dudin’s

later and longer treatise (a posthumously published academic paper

of 1926) also discusses the Merv and Akhal rug types as a group.

Characteristics are “straight”, thin, and durable yarns

[presumeably warps] usually white and rarely grey, white wefts,

and dense knotting. There is again an observation about Akhal rug

pile colors employing considerable white, more than Salor, which

permits their recognition “even at a distance. 29

Central to a consideration of Akhal designs, however, is Semenov’s complaint that Merv carpet-making had shown a “great enthusiasm to imitate the ornamentation of the Akhal Turkmens”, something especially noticeable in the dearth of Merv designs (“almost absent”) in the Merv carpet exhibitions of 1908, 1909, 1910, with an “overwhelming majority” consisting of imitation of Akhal-Tekke and Tejend oasis carpet patterns. 30 The 1908 exhibition is described in great detail by a provincial newspaper – its 80 rugs, khorjin, torba, and chuval; districts and villages of origin; names of the eight prize winners. 31 The first Askhabad exhibition, of 100 rugs (14 from Merv, 8 from Tejend, and one Yomud from Krasnovdosk district) was held in 1912. Some rugs were in “beautiful Pendeh designs”; another although woven in Merv had “a Pendeh pattern”. 32 Appearances: materials Several notations in the literature have to do with Akhal dyes, beginning with the 1888 comment “use of vegetable dyes”. At this same time, dyes were imported from Khiva and Persia; only yellow was made in Akhal (1890). Synthetics had come into use by 1900. The “recent use” of synthetic dyes and “hasty work” were an official complaint of 1903. In the Merv exhibition of 1908 “only eight” rugs (the prize winners) had all natural dyes. (One of the 80 had a natural field and a synthetic border.) Amid the complaints about synthetics there was a positive comment that some weavers were learning to give them up. A ground rule of natural dyes only for future competitive exhibitions was under consideration by the authorities. In 1911 the Askhabad warehouse purchased 26 tons of spring shearing wool for re-sale to rug makers and distribution gratis to poor weavers. Dyes were imported from Bukhara. 33 At least by 1911, imported vegetable dyes were being stocked by the Askhabad warehouse. In 1914 the Akhal Tekkes were making only red and yellow dyes; other colors came via yarns “from the city”. 34 Felkersham noted a “surprisingly rich warm-cherry shade” in antique carpets including those of Akhal, by his time lost because the old method of preparing madder “is almost forgotten”. 35 Appearances: structures “Coarsening” of design, workmanship, and materials began to be noted early on and by the latter 1890’s was perceived as a problem. By the end of the first decade of 20th century there were complaints that it was difficult to see sharp outlines in “new” rugs. Along with these negative comments about the rugs of Akhal, however, there was a positive remark concerning palasi made there: “(they) … are marvelous for their beauty” and are so tightly woven that it takes a long time for a pool of water to seep through. 36 The key aspect of structures, however, is a question about wefting. The Adamov (1930) typology casually mentions Merv carpets as being double-wefted but does not say that about those of Akhal; the inference would be that these are single-wefted. Adamov’s contemporary, V. G. Moshkova, a major field researcher, 1929 – 1945, said so explicitly. 37 Her text provides a great deal of descriptive information concerning Akhal rugs and related products; this does not need repetition (except for a reminder concerning the Akhal marker of equal knot nodes on the back) because her material is well known from an annotated English translation. 38A three word declarative sentence in the Moshkova/Galavin text states that Akhal wefting is single, unlike that of Merv, with its “typical” “double” weft. The O’Bannon commentary calls this a “glaring error”. His criticism rests on review of a group of published Tekke rugs (various attributors; no common definition) of which 159 were double wefted, 57 single wefted. Given the 10 to 1 ratio of Merv to Askhabad weavers -- or the low Akhal share of comparative production statistics (10% in 1900 and 1907, 34% and 19% in 1910 and 1911) -- this result is hardly remarkable. His speculation is that the observation stems from then contemporary rugs in museum collections which Moshkova “must” have seen. But any reading of her text destroys this speculation; throughout, the words “old” and “contemporary” are regularly used, and changes in materials, particularly dyes, over time are noted. Furthermore, speculation isn’t necessary, since the Moshkova text is internally inconsistent, saying elsewhere that at the end of the 19th through the beginning of the 20th century double wefts were employed in “all” Turkmen areas, and that in “old” Turkmen rugs the single weft technique was much more widespread. This distinction seems plausible. In brief, the matter is not glaring; rather, it is murky. A parallel criticism has to do with design, the statement that Akhal fields employed thin dark blue vertical and horizontal lines linking gols, making uniform rectangles, and that such was not a Merv practice, the gols being placed on a “vacant” (ie: empty) field. The O'Bannon commentary sets up the straw man that the lines can’t only be present in Akhal rugs because it is rare to find “antique Tekkes” (undefined) without them. The Moshkova/Galavin text does not use the word “only” and makes the distinction in a discussion of design. Good to remember that by 1908 Merv rugs were using Akhal patterns. A plausible speculation in this instance is also available as to what could have been going on: design spread, uneven survival numbers, and uncertainties about time of manufacture. Perspective Language is a relatively weak instrument to describe a visual art, and care should be taken about limitations of words. This is particularly true for the Moshkova text, given its multiple authorship, its occasions of joint authorship, and its posthumous publication without an evident guiding editorial hand. Yet it remains a major source concerning the rugs of Akhal. So, too are the snippets from various observations of the past posted here. It may be of interest to pursue the somewhat consequential palas manufacture in Akhal, or the checked blue line of one of the Akhal gols illustrated here. But these excavated snippets and the much more substantial Moshkova research need to be tested against the great deal of work done in identifying and linking the characteristics of various Turkmen rug types -- physical attributes as well as stylistic groupings. Both the old words – witness the weaver numbers distinction between Akhal and Merv -- and contemporary findings when combined can shed more light on distinctions among Turkmen rug types: in brief, an continuation of the O’Bannon Moshkova commentary. The archival record does, however, establish one thing. The weavers of Akhal were key players in Tekke carpet design. 1.

Felkersham, Baron A., Staryinnye kovry Srednei Azii, Starye Gody,

October – December, 1914, p. 103.

|