|

|

|

|||||

|

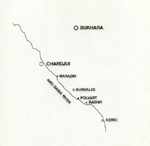

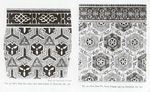

These notes have to do with some rugs from Bukhara, some by Ersari. Behind the scene is the global conqueror, Timur. An allegedly contemporary portrait of him is: A visitor to the imperial tomb in Samarcand in 1908 described a floor textile: “a thick carpet… [with] a space in the middle for the green-veined tombstone…unique in that it fits the circular building exactly…[the design] is strikingly original…a 600 year-old treasure…protected by a linen cover…the lovely ancient design of arabesques and flowers, woven into a white background…” 1 A correspondence with the backdrop in the portrait is apparent.A much earlier (1405) note on the mausoleum mentioned its “figured sarcophagae” and a tomb cover of black jade with inscriptions. 2 There have been latter day visitors : “a dark green floor” 3 and a jade tombstone, 4 no carpet mention. Nor is an 1895 viaitor’s report encouraging in the matter of space for a floor carpet. 5 Count Palen’s details, however, can’t quite be dismissed; a Soviet carpet specialist says the rug has disappeared. 6 Those who have studied Timurid culture point to its assimilation both of Chinese and of Persian (Sasanian) art.7 8 One of the world conqueror’s practices supported this taste; an alleged Timur quote in Hafez is “… and I have depopulated a great number of cities and provinces in order to augment the glory and the richness of Samarcand and of Bokhara, which are ordinary locations of my residences and the seat of my empire…” 9 Timurid style continued into its successor Uzbegs -- in Bukhara, the Mangits: “…the Timourid traditions penetrated into Persia and in the Uzbek States where they kept going for a long time.” 10 Others say the same; for example “Timurid and Uzbek dynasties also patronized Persian art, literature and historical writing”. While Shebanye Khan, creator of Uzbeg power c. 1500 was an admirer of Timurid art, there was a latter day exception; Nasrullah-khan (1826 –1860), who scorned the arts, rejuvenated the military, was very unpopular, and presided over a cultural decline. 11 Bukhara was ever of consequence, both regional trade hub and manufacturing center. Its products are mentioned in medaeval chronicles -- Zandaniji cloth, Yazdi cloth, cushions, prayer rugs, khalats (robes), door hangings, and hanging tapestries. A passage in Yakut was misread (in 1947) to include carpets, a mistake soon corrected (in 1958), a translator’s failure to see a prefix; the mistranslated word meant hanging tapestries. 12 Translations of deep past terms for various textiles are tricky; words shifted in meaning over time and between languages, plus the fact that copying corrupted texts. 13 Of the 40 or so Bukhara guilds with by-laws (rissala) 32 produced manufactured items; among this corps du métier were weavers, silk makers, velvet makers, “painters” of saddles, felt makers, and silk dyers.14 (The dyers were Jewish.) This enterprise continued. In 1823, a visitor mentioned “all sorts of cotton fabric” as well as silk; 15 fabric production included mixed silk and cotton; at this same time another observer remarked that “Russian stuffs” were providing the patterns. 16 Cotton (dyed and colored) and stuffs of silk were being produced but without workplaces with more than 20 employees. 17 The product was high style, as can be seen in the velvet and gold brocade saddle cover, below, photographed in 1885, typical of items made for the Emir and his pals. Trade was intraregional. Some Bukhara exports did reach Europe via a northern overland route through Orenberg; carpets, however, were a trivial presence. For example, a customs manifest in 1819: “5 rugs, 54 ordinary shawls, Cachmere shawls.” 18 The main trade consisted of cotton products, ‘lames’ of gold and silver, cochineal, coral, gold thread, velvet robes, silks, and horses;19 trade along the more direct Khiva route, in spite of the bad relations between the two khanates, carried the same bulk items, raw and finished cotton goods.20 Later in the century the route continued to be unsafe, infested by robbers (nomadic Kazaks), and somewhat problematic for trade purposes. 21 Skepticism should greet any claim that rugs mattered much on either of these pre-Russian conquest trade routes. While Bukhara city was important so were three other places: Chardjui, (from Tchhar-djui, meaning four brooks, Amu Daria tributaries), 22 the khanate’s second city; Karshi, a commercial hub inland from the river and in due course connected to Bukhara and Kerki by railroad spurs; and, Kerki, the river’s upper navigation limit, the departure point for trade to Afghanistan. People of the steppes have always been engaged in complementary commerce with the oasis centers, the exchanging of raw and finished articles such as rugs and felts for arms, metal, and artisan products. 23 An early datum on intra-regional trade showed up in an 1869 Russian government survey of the then new colonial territory -- standard Imperial practice using interdisciplinary teams including an artist 24 (thought to be an aid to research) -- an expedition incidentally producing illustrations of Bukhara carpets (below); the Simakov team had no knowledge about and probably no interest in carpets, the text merely reporting what the team was told. The Simakov book is significant in that the rugs were in Tashkent, well to the north of Bukhara, their presence a measure of regional carpet commerce. 25 The Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries Although Samarcand was the capital the Emir (c. 1879 portrait above, sporting Russian medals) lived in Bukhara. Small cities also were important. Chardjui (in 1820) 1000 houses, 26 1834 population between four and five thousand, with a bazaar of “cloth and horseclothes”, 2 -- 3 thousand people present; 27 later (c. 1880) on the order of four thousand and a “big enough” commerce with Turkmens, consisting of grains, knives, saddle covers, clothing and utensils, and purchases of horses, sheep, and felt; 28 at the end of the century an important transshipment point, incoming by river, outgoing by rail. 29 It also was the site of an important fortress; the beg (c. 1880, below) was the Emir’s fourth, pious, son. Some observations about Karshi mention a hundreds yards long street of wool bazaars, a chief mart for “cattle”, and its being locus of a “vast” number of Turkmen carpets and horse coverings for sale (1843); 30 there were twenty thousand resident families, Tajiks and Uzbegs, and a doubled winter population, mostly Uzbegs (c. 1820); 31 Karshi was the khanate’s second center, “a very important commercial town”. Bukhara city in 1843 was no different: a bazaar with morning and evening carpet sections; 32 no “considerable manufacturies”, work taking place at home, a product line primarily of dyed mixed color cotton, plus silk and “all kinds of clothing. 33 There are many similar travel account descriptions. The khanate was an ethnic stew 34 of different peoples in varying locations -- small cities, and auls (hamlets) on the steppes -- in two major ethnic groups, Iranians and Turks, using Farsi and Turki, with the majority of city folk bilingual. All had a common history, culture, and (for most) religion. Identity was with clan, family, location, and local ruler: “…an agglomeration of towns, villages, rural districts, and nomadic and seminomadic tribes, held together loosely by economic ties but primarily by loyalty to a common dynasty enforced through political and military sanctions.” 35 Russian overlords and western visitors sometimes used the offensive term Sart (yellow dog) to designate Uzbeg-speaking city dwellers. In fact they could have been either Turks or Iranians. Some outsider names for peoples -- Uzbeg-Turkmens, Khirgiz-Uzbegs and the like are for the most part off the mark. Ethnicity and language were not always an identity; there are occasional instances of neighboring villages of the same ethnicity with one speaking Farsi and the other Turki. V. V. Stasov knew about such matters and in his review of the Simakov book observed: “Central Asian art presents nothing unique, intact, singular. No, on the contrary, it is a conglomeration of creative activity of varying nationalities: Turks, Iranians, Hindustanis, Arabs, Mongols and several other tribal groups.” 36 Some members of the Turkmen Academy of Arts and Sciences hold the same view, and include Turkmen carpets in it. 37 The Bukhara Turkmens The Amu Daria littoral, especially its left bank, was Turkmen territory, many groups known under the rubric, Ersari, a clan of a main Oghuz division, Kinik. 38 William Wood’s ethnohistory article 39 notes Ersari movements in the Turkmens substantial departure from the Mangishlak peninsula; in brief, they were early out (17th c.), some initially to Khorezm (Khiva) and subsequently to Bukhara, there certainly by the early 1700’s, to become sedentary and agricultural. “The Turkomans are established all along the length of the river in a corridor of four or five day’s travel.” 40 Others arrived in Bukhara later by a less direct route via an intermediate stop on the southern rim of Turkmen territory. There is some dispute among area specialists as to when Turkmens generally became sedentary, the majority arguing early, a minority,41 later. This issue is moot as far as carpets are concerned; substantial settledness was a fact well before the time when the rugs around nowadays were created. Glimpses of the whereabouts of the Bukhara Turkmens in the travel literature note their sedentary nature, viz. (in 1823) “Since twenty years ago this people had begun to get used to fixed residences.” 42 The south bank of the Amu was irrigated, for cotton, its agriculturists allegedly Uzbeg and Karakalpak, with Turkmens living on the steppes fringe, the Ata in fixed houses and Ersaris in hamlets which moved from one pasture to another. 43 Sightseers were not the only describers. Some, like Simakov in Sir Daria oblast’ north of Bukhara, were on the purposeful mission of inventorying new colonial territory. Such a one was Capt. Komarov who reported on the Amu Daria extensive irrigation, the dominant agricultural economic activity (cotton, wheat, barley with cotton using half the cultivated land), and naming four Ersari clans in 54 subdivisions. 44 Tumanovich, writing in a Turkmen academic journal of 1926, identifies the clans as Uluk, Gunyash, Kara, Bek-Aul’. 45 The Carpet Literature Observations concerning Bukhara rugs appear in the early 20th c. Russian carpet literature. Bedrock here is the big four -- Bogoliubov, Dudin, Felkersham, and Semenov. The reports of the latter, better three say more or less the same thing. S. M. Dudin gave a nod to Semenov’s expertise in that he had spent more time in the region. 46 Felkersham was careful to stress the uncertainties of who, what, where, and when; he was not alone, the other authors saying the same thing a bit less pointedly. Felkersham also surfaced a significant fact: Kerki and Bashir carpet-making as “an important craft” began “a mere 40 years ago.”47 That is, the 1870’s. The gist of Semenov is: - Kerki was the principal production center of low priced marketplace competitive rugs, and included the kishlak (small political jurisdiction) Kizil-Ayak (between Kerki and the river); the kishlak Bashir, the older rugs of which are an attractive terra cotta color; the kishlak Tcakur near Kerki; and, the kishlak Charchangi with rugs known by that name and in typical Kizil-Ayak designs. - Palas were made in Denaus and Karshi bekdoms, those of Karshi being regarded as the best of Central Asia, and labeled “Arab” due to the weavers’ alleged descent from Arabs; nomadic “Kirgiz-Uzbeg” called Kattagan also made palas in the steppes south-east of Bukhara. Shakmisydz in the same bekdom was the source of beautiful silk fabric, sometimes called Iraki, folklore (echoed in the travel literature) the makers having been descendants of those brought into the area in the distant past. - In Bukhara the demand for Bashir carpets exceeded that for any other type; these inexpensive carpets were especially popular with the “working” class; some of low quality were made in the workshops of the Emir, mostly as presents; and, in general Bashir carpets in the Bukhara khanate can be viewed as “government carpets”. Neglected Works One is an exhibition catalogue 48 which in spite of understandable limitations of old-fashioned text and lack of color illustration is rich with 54 illustrations showing the various designs of the khanate, together with a good map, and offering a good panorama of Bukhara carpet design. Another is the only rug book written by Turkmens. 49 The text (some in English) does not say much about Ersari carpets, but a number are illustrated and accompanied by design and category names (Kizil-Ayak, Bashir, Kerki). The illustration below is a Kizil-Ayak carpet made in 1935, looking much like one of the vintage Ersari types of the marketplace; the next illustration is of a rug made in 1973, also called Kizil Ayak. Nothing is easy. What, Who and Where The Bukhara khanate product is a gallimaufry but two of its elements are straight-forward. One is the Kizil Ayak (both a place and a clan name, best taken as an identity) group of rugs. The Wood article on the Turkmen diaspora takes the Bukhara Kizil Ayak first to the southern rim of Turkmen country, followed later by a move north to Bukhara. That some of their product resembles that of the southern rim (Tekke, Saryk, etc.) is to be expected and that it could have continued not surprising. Another has to do with where the rugs were made. Some years ago a contentious HALI article attacked an earlier essay which contended that some came from the city or within the Bukhara cultural sphere, plus an assertion that there “must have been” urban carpet-making for several centuries.50 The attack marshaled a list of travel account observations which did not mention carpet-making in Bukhara city, and was accompanied by a reference to an unsubstantiated claim in a latter day Soviet carpet book (“… pile weaving was not practiced even in its [Bukhara’s] vicinity, let alone in the town itself”).51 The travel account argument is not worth making. The affirmation bears the burden of proof, and the urban carpet-making assertion did not have any. There is an additional reason which is not to bother with recitation of null sets; in this case due to inability to choose among (a) absence of rugs; (b) presence of rugs, missed; and, (c) rugs seen but not mentioned. Much more serious, the rebuttal article 52 contains a flat misrepresentation of the Semenov text. It was the Emir’s “workshops”, plural, not “one” of them, which made rugs; the text remarked that Bashir carpets were run-or-the-mill and bought by the “working class”; there is nothing about upper class patronage. Semenov did use the term “state carpets” but in a very different sense: “ …in general Bashir carpets in Bokhara khanate in the full sense of the word are government carpets (gilam-i-davlyati)”. These Uzbeg words are “government carpets”, 53which the Russian exactly reproduces. The comment is not complementary but rather something along the lines of the Americanism, “it’s good enough for government work.” The Emir gave away cheap stuff; smart man. Although Semenov, well grounded in the field and speaking Uzbeg, may possibly have misperceived, what is unacceptable is flagrant mistranslation and misinterpretation turning his statements upside down. The matter of Bukhara carpets also furnishes two cases in point illustrating another difficulty: the interpretation of travel accounts. One early 20th c. description reads: “Bukhara is famous for its rugs, its silks and its embroideries of silk on cotton…The rugs and embroideries are in unique shades of red, not found elsewhere.” Also mentioned is that there are “enormous” rug warehouses; and, each family house has a loom, a family employing two or three out of the total of 10 – 12 designs, overall only four or five in use. 54 Sounds good, persuasive in its details, but when probed unravels -- what did the house looms make and where were the houses, and how much of the material warehoused was transit trade? Carmine red or terra cotta red? And so forth. Another account (1894/5) observes: “(on the bazaar) We saw none of that peculiar pattern so familiar to s all as ‘Bokhara’ carpets. I am told that they are made in the outlying towns of the province. There were none even in Amir’s palace.” But, the same text 22 pages earlier says (concerning the Emir’s palace) “Bokhara carpets of rare quality and great value were tossed here and there…” 55 Is Mr. Shoemaker from Cincinnati Ohio pointing out that the Turkmen type rug known as Bukhara in the export market is made in the khanate’s outlying districts and that some other, product is gracing the Emir’s palace? Does he know enough to be making such a distinction or is he simply writing travelogue words? A perspective a la that of Stasov and of Asgabat scholars is probably best. The approach for the casual student of Bukhara carpets -- someone without an advanced degree in Central Asian studies, Asian art, and lacking Farsi, Turki, or Arabic script – should be to relax and enjoy the diversity of their art. The concept “Bukhara cultural sphere” is exactly right and the sensible perspective. Today’s nomenclature of Central Asia is quite different, with its Soviet imposed reconfiguration into arbitrary political jurisdictions and so-called national republics. 56 Farsi was relabeled Tajik; Turkic splintered into Uzbeg, Kazak, and Turkmen. The Soviet rearranging distorts any view of the folk of the weaving hey-day, and books by Soviet authors are difficult to parse with the earlier literature. Turkmen Soviet authors are somewhat less doctrinaire and the better sources. Even though the past is complex, obscure, and frequently distorted, a proper outlook has been around for 30 years, in the form of an essay by Konig. He got it straight -- the common artistic heritage and the changing stew of clans, ethnicity, life style, place names, and political jurisdictions. 57 And had the wit to use one of the better sources, Pirkuleva, 58 an Asgabat Turkmen. The essay contains considerable data about weaving technics; this is good, and both the Moshkova and Pirkuleva reports also have this information. Not all is consistent, however. There is also the problem that no weaving technique is unique to a single group. Konig set up a four-part organization of the Ersari category . The two most clearly defined categories, Ersari and Kizil Ayak, appear in the motif sketches above-- taken from the old Russian literature, those in the top half “Ersari” and those in the bottom “Kizil Ayak”. The two middle categories are intermediate and appropriately cautious. The conflation of the Kizil-Ayak and Bashir categories appears regularly in the old literature 59 and yet the Bashir and Kerki type names could be considered separate categories, as late as 1934. 60 Central Asian Art History By a commodius vicus of recirculation 61 through the complexities of culture, shifting sands of history, and the many faceted rugs, one returns to Timur. The texiles of his era have long been known in Islamic art circles. 62 There are various sources; one is miniatures (examples below). Another is textile fragments, showing grids or rosettes which touch with blossoms at the point of contact, a Sasanian echo. 63 Yet another is manuscript illustrations: There were two rather different styles -- floral and curvilinear, loosely speaking, Persianate; and geometricized floral in an all-over repeat employing two sets of motifs the one larger, the other smaller, loosely speaking, Turkic. Borders frequently involved “characteristic Timurid band of flowers”. 64 At a very general level, this is the case in many rug genres. And in Bukhara, stemming from its artistic heritage. It is not too much of a stretch to see the Timurid style in some Ersari rugs. The argument, which is only circumstantial, is simple: it is not unreasonable to speculate that settled Turkmens weavers could pick up the Timurid version of all over geometric patterns. This proximity argument also applies to some motifs of the Khiva Chodor. Some Ersari gols of today may have come about later than one might think. Afterword The teapot tempest concerning Bukhara rugs may hold one more little lesson -- the bias that city work is commercial and somehow unworthy, and that only “tribal” products have merit, along the lines of the used car which was owned by a little old lady who drove it only once a week to church. This view assumes a false dichotomy -- city one thing, tribal, another. Reality is that country folk wove rugs partly for income and accordingly wove for city folk. And, country weavers adopted designs and patterns of city style if they liked them. Particularly in Bukhara circumstances it is hard to imagine anything other than this two way street with cross-overs of pattern and motif.

1 Phalen, K. K., Memories of 1908—1909, trans N. J. Couriss, London, 1964, PAGE. 2 Bouvat, Lucien, Essai sur la civilization Timurid, Journal Asiatique, #2, April – Juin, 1926, p. 255. 3 Khanikov, Nikolai, Bokhara: Its Amir and Its People, trans. C. A. de Bode, 1845, p. 131. 4 Durrieux, A. and Fauvelle, R., Samarkand, La Bien Guardee, Paris, 1901. 5 Shoemaker, M. M., The Sealed Provinces of the Czar, 1895, p. 132. 6 Elena Tsareva, in conversation. 7 Bouvat, Lucien, op. cit., p. 253. 8 Meyendorf, Georges de, Voyage d’Orenbourg a Boukhara fait en 1820, 1826, p. 288. 9 De Lacy, Silvestre, Histoire des Poets, “Douletschah bar-Alaeddoulet, per Khodja Hafez Schirazi”, Notices et Extraits des Manuscrits, 1799, p. 241. 10 Bouvat, op. cit., p. 258. 11 Allworth, Edward A., The Modern Uzbeks, 1990, p. 13, p. 111. 12 Frye, Richard N., The History of Bukhara, 1954, p. 15, pp. 19-20, p. 119. 13 For example, articles in Ars Islamica, Vol 1, Vol 2, Vol 11-12. 14 Gavrilov, Micel, trans. J. Castagne, Les Corps de métiers en Asie Centrale, extract from Revue des Etudes Islamiques, Vol II,, 1928. 15 Iakovlev, P. L., “Fragments of a Journey in Bukharia”, Nouvelles Annales des Voyages, Paris, 1823, p. 165. 16 De Larenaudiere, Nouvelles Annales des Voyages, (a survey article) Vol. XXIX, 1826, p. 316-17. 17 Iakovlev, op. cit., Vol XVIII, p. 156, p. 165; Reception d’une Caravane a Orenburg, Nouvelles Annals des Voyages, second series, Vol 19/20, 1831, p. 127. 18 Meyendorf, op. cit., p. 241. 19 Iakovlev, op. cit., p, 167 20 ibid., p.164, p. 167, 169; Embasy to Bucharia by Dr. Eversman, Physician, and Mr. Jacovlew, Secretary to the Embasy, Russian Missions to the Interior of Asia, London 1823, p. 40. 21 Shavrov, K. A., Put’ v Tsentral’nayi Azii, St. Petersburg, 1871, p. 39. 22 Sidi Ali Reis, Travels … of the Turkish Admiral, (1553 –1556), trans. A. Vambery, 1899, p. 78. 23 Centlivres, Pierre, Les Relations Nomades-Sedentaires, in Seminaire sur les nomadism en Asie Centrale, Berne, l977, p. 77/78. 24 S. M. Dudin later came to Central Asia in the same role, illustrating a good deal of its architecture. 25 Simakov, N. E., L’Art de l’Asie Central, Recueil de l’Art Decoratif de l’Asie Central, Plate #4 -- #7, St. Petersburg, 1883. 26 Meyendorf, op. cit., p. 156. 27 Burnes, Alexander, Travels into Bokhara, 1834, Vol. II, p.2. 28 Capt. Weil, La Tourkmenie et les Tourkmenes, trans. of article in Voienny Sbornik. 29 Curtis, William Eleroy, Turkestan, the Heart of Asia, 1911, p. 111, p. 113. 30 Khanikov, op, cit., p. 141. 31 Moorcroft, Wm. and Trebeck, George, Travels, 1841, p. 503. 32 Khanikov, op. cit., p. 117 ff. 33 Eversmann and Jakoview, op. cit., p. 55. 34 Matley, Ian M., “Ethnic Groups of the Bukharian State ca. 1920 and the Question of Nationality”, in Allworth, The Nationality Question in Central Asia., p. 141. 35 Becker, Seymour, “National Consciousness and the Politics of The Bukhara Peoples’s Republic”, The Nationality Question in Soviet Central Asia, ed. Edward Allworth, 1973; a number of papers in this collection make the same point. 36 Stasov, V. V., Sobranie Sochinenii, Vol. II, St. Petersburg, 1894, p. 700. 37 Shakhberdieva, D., “Turkmen National Carpet Patterns and Their Regeneration During the Years of Independence of Turkmenistan”; Zaletayev, V. S., “Elements and Symbols of Animalism in Ornaments of a Turkmen Carpet”; Niyazi, N. N., “Origin and History of Denomination of Turkmen Carpets’ Ornaments”; papers at the symposium on the art of Turkmen carpets, Asgabat, May, 1996. 38 Rivers, L., Reference Sheets, People of the Rug, Textile Museum Convention, Oct. 16—18, 1998. 39 Wood, William, “Turkmen Ethnohistory”, in Vanishing Jewels, 1990. 40 Histoire de l’Asie Centrale par Mir Abdoul Kerim Boukhary, 1740 –1818, trans. Ch. Schefer, p. 171. 41 Bregel, Yu., “Nomadic and Sedentary Elements Among the Turkmens”, Central Asian Journal, Vol XXV, #1-2, 1981. 42 Iakovlev, op. cit., p. 162. 43 Moser, Henri, A Travers l’Asie Central, 1885, p. 206. 44 Komarov, Capt. G.-Sh., Karatkia Statisticheskia Svedeniya o plemen ersari..., Sbornik geografieskikh, topografischneskikh i satisticheskikh materialov po Azii, Vol. 25, p. 278 ff. 45 Tumanovich, O., Turkmenistan i…, Materaly k izucheniu istorii i etnografii, Askabad, 1926, p. 86. 46 Dudin, S. M., Kovrovye izdelina Srednei Azii, Sbornik Muzeya Antropologii i Etnografii, t. VII, p. 103. 47 Felkersham, Baron A., Starinnie Kovry Srednei Azii, Starye Gody, April-May, 1915, pp. 34-37. 48 Jones, H. M. and Boucher, J. W., The Ersari and Their Weavings, 1975. 49 Dobodov, N. and Khodzhamukhamedov, N., Kovry Turkmenstan, Ashkhabad, 1973. 50 Tompson, J., op. cit., p. 180. 51 Tsareva, Elena, Rugs and Carpets from Central Asia, Leningrad, 1984, p. 6. 52 Pinner, Robert, HALI, Vol 3 no 4, p. 294 ff. p. 300. The best face that can be put upon the almost complete reversal of the Semenov text is an egregiously poor translation. There is other mischief with respect to references to the Moshkova text; perhaps the facts were being fitted to the policy. 53 Per Edward Allworth, Columbia University. 54 Curtis, Wm. E., Turkestan, the Heart of Asia, New York, 1911, p.167, 168. 55 Shoemaker, op. cit. 56 Barrett, Robert J., “Convergence and Nationality Literature of Central Asia”, in Allworth, Nationality Question…, op. cit., p. 20. 57 Konig, Hans, “Ersari Carpets”, Turkmen, ed. Thompson and Mackie, 1980, p. 190 ff. 58 Pirkuleva, Anna. Konig used either a German translation or the Russian of “Kovrovoe tkachestva turkmen doliny srednei amu-dar’i”, Material’naya kul’tura narodov Srednei Azii i Kazakhstana, Moscow, 1966; a long article with a considerable review of the Imperial literature, with Dudin considered the best; a shorter and easier to handle essay, same substance but without a literature review, is her Domashnie promysly i remesla Turkmen doliny srednei Amydar’i vo vtorou polovine XIX – nachale XX v., Ashkhabad, 1973. 59 See for example, Logofet, D. M., Na Granitsakh Srednei Azii, Vol. I, 1909, p. 124-25. 60 Adamov, A. K., Sovietskie Kovry i Ikh Eksport, 1934. 18. 61 Thank you Mr. Joyce. 62 Briggs, Amy, “Timurid Carpets”, Ars Islamica, Vol. VII, Pt. 1, p. 20 ff. 63 Lentz, Thomas, and Lowry, Glenn, Timur and the Princely Vision, 1989, pp. 216-18. 64 Martin, F. R., Miniatures From the Period of Timur, Ms. Of Poems of Sultan Ahmad Jalair, 1926, p. 9.

|