|

This note

has to do with a 1986 Uzbek survey by Sadykova et al of Uzbekistan’s kustar’ (home craft) industry in the 19th and 20th The book can usefully be read bearing in mind the work of V. G. Moshkova et al.[2] Although much of its material stems from field research carried out between 1929 and 1945, it acknowledges that the Uzbek text is substantially dependent upon four pre-revolution publications, among them that of Baton Felkersham, which deals to a considerable extent with the matter of Uzbek carpets. Felkersham, Moshkova, and Sadykova all use the geographic ordering principle of “Uzbekistan”, not quite the same in the three studies. Both geographic scope and administrative nomenclature differ. Ethnicity is blurry. It is also true that where a rug was observed does not necessarily mean it was made there, or connect to a clan, and it is wise to view the clans themselves as of mixed ethnicity. People of alleged arab descent, self-styled Turkmen Uzbegs, Karakalpaks,[3] and others are mentioned. The Moshkova text treats four subsidiary areas of Uzbekistan and not the whole: Samarcand , the Nurata basin, the Fergana valley, and Kashkadar. This sketch map shows the geography and administration of Imperial Russia; the best maps to use for tracking down place names are those in the English version of Moshkova.

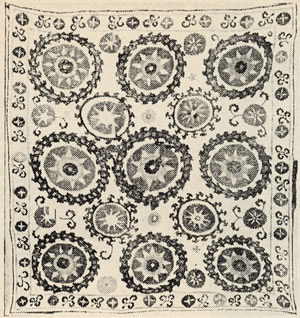

Sadykova et al These illustrations, none of them pile items, show some of the design characteristics of various Uzbek kustar’ textile products.

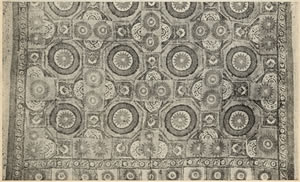

The Sadykova text reads as follows in slightly rough translation “History has developed the distinctive features of the furnishings in the abodes of the people of Uzbekistan, as well as all Central Asia – plentiful carpets, felt manufactures, but also various mats, used fairly often with modest assortments of wooden furniture. While frequently important in the traditional lifestyle of settled groups, but chiefly in nomadic living – carpets, palasi, felt, in our times retain their functional purpose and continue as works of native art. “Traditional carpet-making of the peoples of Uzbekistan is deep seated and abundant. Well known in three categories, they are: short-napped carpets gilam, high pile dzhulkhirs (zhulkhirs), and palas [flatwoven] fabrics, extremely varied in techniques of execution and coloring. “Carpet-making as women’s domestic economic activity was developed in almost each livestock-breeding and livestock-agricultural area. Production of master carpet-makers (gilamchi) or gilambof, gilamduz for the most part satisfactorily met the needs of household use; selling in city markets remaining only a small portion. “A highly developed state of native creative activity led to its being one of the leading employment positions among the artistic crafts of Uzbekistan. The development of women’s handicraft art drew into their life its own beauty, diverse in its own traditional variations, at the same time always retaining local distinctive qualities. “The carpet areas of Bukhara were distinguished by colorful and diverse designs, large size, and high pile. In certain places in Samarcand and Sir Daria oblast’s [administrative areas] more plain [simpler] carpets with uncomplicated patterns, in a reddish-dark-blue range were made. There are few varieties of Samarcand carpets. Interesting tightly woven carpets with close cropped pile, in the center field of which usually [were] arranged eight-sided medallions filling in with the same type of design. The most popular medallion was kalkon nushka (with the bukv. [???] design in the border.) In particular parts of Samarcand oblast’ there was a wide range and proliferation of carpets, in the central field of which could be discerned narrow ornamental stripes in large oblique diamond shapes with a blending of the same type of medallions. The ornamentation consisted for the most part of rows of rombov [diamond shapes].[4] Brevity and expressiveness – such were the esthetic parameters of these rugs. “The Nurata area was distinguished by an output consisting entirely of fluffy light carpets (zhulkhirs) of medium size. They have less density, cheaper [lesser quality] fabric, and looseness. The composition of the central field forms longitudinal stripes, filled in with a repeat pattern. The border’s appearance is that of a row of rhombovs and triangles [which] reinforce the geometric evenness of the design. “The well-known art masters of the kishlaks [hamlets] of Aim, Dardak in Andizhan oblasti were involved. Their carpets were of a successful consistency of strict red-dark blue coloring, making it possible to enjoy firm, durable, and beautiful vegetable handsome madder, ruyan, and indigo, up to the end of the 19th c. when [they] were replaced by aniline dyes. “In a number of Fergana villages several semi-nomadic groups of Kirgiz and Uzbek populations make carpets of red and dark blue deep shades. Skillful blending by refined processing produced a wonderful combination of scarlet, strawberry, dark-red with a saturated dark- and bright-blue. The composition of the carpets was formed by a central field and border framework [made] out of one primary and two accompanying stripes. The central field was decorated with medallions, ornamental motifs, sometimes involving straight or breaking lines, with figures in the form of quadratic diamonds with ornamental motifs inside, stripes, infilling of repeating designs, etcetera. The carrying out of linear-plant designs gave an austere beauty to these carpets. Sometimes the central field was decorated with a medallion or image of a flowering bush, vases with flowers – typical for the decorative art of Central Asia. Carpets with such designs were called Kashgari [a city east of Bukhara and Samarcand]. “Palasi were extensively employed in daily life. The best were considered to be Bukhari. They were of large size, with prominent designs in white, red and yellow. The manufacture of palas distinguishes itself from the techniques of carpet-making. A smooth surface from interlacing yarns of the base and wefts, whereas the surface of pile carpets forms an additional layer of yarns. The people in certain kishlaks near Shakhrisab and Karshi were engaged in their manufacture. “Palasi manufacturing produced two types: dorozhki [bands] fabrics from narrow moveable looms, and large palasi in one piece. Narrow palasi bands and dorozhki were sewn together and from them were created distinctive palasi, bags, small bags, window curtains. Also made were ropes, lassos, felt hats, socks, fabric from camel wool and goat down. “Woolen fabric from the city of Ura-Tube was particularly renowned -- homespun materials from sheep and camel wool, in particular, for the manufacture of the men’s upper garment, chakmon, put on over the quilted batting of a khalat. This material also went as warm linings, kebanak, into woolen khalats. “Great use was made in daily life of felt namats [numuds]. These covered yurts, covered the floor together with carpets, and were employed for pack loads. The production of felt primarily engaged women. Washing and beating the wool, sprinkling water, spreading [it] in even layers for the making of felts and mats (chii) which are rolled and tied up with cords. Making a roll was done by beating [the material] with the hand, [then] rolled and shaken, and moistened from time to time with water. After some time the package was turned upside down, jumped onto, filled [saturated] with water, navivali, and pressed with a wooden rolling pin until finished as a koshma. Koshmas were white, grey, and colored; especially valuable were the thick and dense white ones. “An independent commerce existed in the making of insoles for rubbers, boots, and other shoes. Insoles were made from koshmas and were embroidered along the edge and in the center with different colored cotton yarns. Craftsmen always have had a significant stock of insoles for attracting buyers by the brightness and intricacy of embroidery. In Tashkent there were 40 craftsmen who made inner soles. “The craftsman, patakchi, sat; with feet he pressed down on the material beneath a small table and with very rapid hands embroidered. In addition to small tables, ish taxta, the craftsmen used scissors, kaichi, and a chain stitch hooked needle, kruchka bigiz. The pattern was not copied but made up on the spot by eye. They used Kashgar koshmas – kashgar namat – (from Osha) in blue, yellow, red and white colors, as well as thin koshmas. “The inner sole was formed from two pieces of felt, between which were sewn layerings of reeds, buira chub, increasing the strength of the soles. Plastic was glued together with paste, sirach. Except for insoles already edged, items were fitted for the purchaser. “In our times almost all elements of traditional carpet, palas, and felt making survive. Carpet-making is developing an industrial base in the republic. Carpet undertakings are present in Samarcand, Sarkhandar, Khorezm, Kashkadar oblasts, the Fergana valley, and the Karakalpak ASSR. Original high pile carpets –zhulkurs – with good looking delightful color -- the same as before -- continue the fame of the Samarcand masters. They have not forgotten the complicated techniques gashari, terma, [widely used, but no details of weave specified] of Sukhandar palas-making. The patterns of koshma with expressive half-diamond ornamentation continues popular in Surkhandar, Karakalpak, Khorezm, and the Fergana valley. “ Felkersham [5] The baron, who had spent time in the region, has this to say: “Whether they are nomadic or settled, all Uzbeks make carpets. In Turkestan, [a large territory encompassing several imperial provinces] only those carpets on which the pattern is visible on the right side but not on the reverse are called Uzbek carpets (S. M. Dudin). The Uzbeks use only horizontal looms. The wool is usually quite coarse and of uneven quality, since the Uzbeks raise sheep whose wool is not particularly fine-stapled, and they use wool from a number of different breeds. A unique characteristic of Uzbek palasi, met nowhere else in Central Asia, is the fact that they are sewn together from separate strips. “One of the most widely used patterns is a design of rhombus shapes and of stripes with hook-shaped projections. This pattern also occurs frequently in Afghanistan, but with one difference – the inner field of the rhombuses are treated differently. Incidentally, it should be pointed out that according to S. M. Dudin, the namazlik or prayer rug is called in Uzbek a siluche, while the runner, an iolam among the Yomuds, is called a kur. “Whereas only the nomadic tribes among the Turkmen and the Kirghiz make carpets, among the Uzbeks this work is done by the settled tribes, or to be more accurate, the carpets made by them are of higher quality and are therefore more noteworthy. This explains why in Turkestan and even in the Caucasus these carpets are not called Uzbek, but are usually named after the place of manufacture, namely ‘Bashir’ and ‘Kerki’. However these same carpets are also sometimes named after the Uzbek tribe that produced them, for instance “Kizyl-Ayak” (Dudin). It should, however, be noted that one Uzbek tribe is itself called “Bashir”, and that the name “Bashir” and “Kizyl-Ayak” also refer to Turkmen tribes (according to Bogoliubov, for example). All of which demonstrates that these questions have yet to be clarified. “Turning now to specific Uzbek tribes, we note, first of all, that the Bashir and Kizyl-Ayak tribes roam in Turkestan principally near the Bukhara cities of Kerki and Bashir, as well as in neighboring Russian districts. There are only slight differences between the carpets of these two tribes, and both comprise a group which in the West are called Bukhara carpets. Within this group of carpets the Bukhara and Samarkand traders call those with a simpler geometric ornament somewhat reminiscent of Tekke carpets (for instance, with octagons and in only a few colors with red predominating) Kizyl-Ayak. Those with a more complex pattern of flowers and suchlike, and with a greater range of colors they call Bashir carpets. This question has not yet been researched in detail, but it may be of some consolation it may be said that no antique carpets of either type appear to have survived, and that in general carpet production as an important craft appeared among these tribes, as well as among the Kerki and Bashirs, a mere forty years ago. Consequently, these carpets attract the attention of scholars and enthusiasts less than other Central Asian types. It would appear that the Uzbeks’ old carpets have not been preserved because they were crude and inartistic, and even in their own time were considered of little value. Generally, old carpets attributed to the Uzbeks are extremely rare. We include a reproduction of a prayer rug, the originality of which is immediately apparent.

“With reference to the two places named above, I should explain that Kerki is a small Bukhara settlement or town situated on the left bank of the Amu-Daria. Above the town looms a fortress and castle, the residence of the bek [governor]. The people of Bukhara consider Kerki an important fortification, and today it is the point through which large quantities of merchandise enter Bukhara from Afghan Turkestan, and Bukharian and Russian goods enter Afghanistan.[6] Bashir is an enormous settlement on the right bank of the Amu-Dari between Kerki and Burdalyk, and it too lies within the territory of the Bukhara khanate. There are over 4,000 households in Bashir, and almost half the population is employed in the production of carpets and the half-silk fabric known as alacha. “According to information gathered for us in 1902 by K. Laurenti, in Kerki and Bashir only women weave carpets, while dyeing and the threading of the looms is the responsibility of the men. At least part of the wool is imported from Afghanistan, which explains why these carpets are finer and brighter than other Uzbek carpets. In addition to clipped carpets, many palasi are also produced here, on the horizontal looms placed directly on the ground that are used everywhere in Central Asia. Actually, they cannot even be called looms, so primitive is their construction. The yarn is simply stretched on pegs hammered into the ground at equal distances. Even big carpets, from five to ten arshins [11’ 8” to 23’ 4”] long and four arshins [9’ 4”] wide are made on this contraption. A large carpet can be manufactured much faster than one might think, requiring just fifteen to twenty days. From three to five women are needed to work a small carpet, while ten, twenty, and even more, are required for a large carpet. Goat and camel hair are never used, and the wool is dyed locally. Earlier, before the appearance here of alizarin and analin dyes they used only vegetable dyes imported from India. The principal shade in Kizyl-Ayak carpets is always a dark raspberry red, and since the best white wool is used for the warp threads, the end fringe is white. A gray or even black selvage indicates a carpet of inferior quality. “The Kipchaks. The Kipchak Uzbeks roam in the Zaryavshin valley. They should not be confused with the Kara-Kirghiz tribe of the same name that lives in the Fergana region, primarily in Andizhan district. We have no detailed information on their carpet production, but we can state with certainty that their work has little merit. “The Kungrat tribe is particularly noteworthy for the production of luxurious palasi with plant motif designs, whereas their clipped carpets are little different than the ordinary goods made by the other nomadic Uzbeks. “The Kara Kalpaks, whose numerous population once gave them an important role in Turkestan but who today number a mere 60,000, roam in the Amu-Daria delta, in small groups close to Samarkand and the left bank of the Syr-Dari, north east of Kokand. Despite a number of racial characteristics they share with other Uzbek tribes, the Kara Kalpaks differ in their ethnographic makeup and so are sometimes considered a specific nationality. Their carpets are always inferior in quality and coarser than other Uzbek carpets; the pile is very long and uneven, the design unrefined and inadequately worked out – in short, they tend to produce a rather crude impression. However, at one time this was not the case and one can find examples of excellent quality among the old carpets.” The travel literature offers a glimpse which places the Sadykov description of rugs with nomadic Uzbeks, well back into the 19th c. as follows: having more tasteful interiors than the Khirgiz �� for the Uzbegs hang along the sides small carpets of home manufacture; and though the work be coarse, and the colours generally of a somber hue, dark red and brick colour in particular,�� [7] Some perspective There have been major changes in the borders of “Uzbekistan” since the imperial period in which Felkersham wrote; significant portions of its then far west and far east are gone and are free standing nationality republics. Much study and analysis of the Turkmen rug genre has taken place since the publication of the three books mentioned here, and it is hard not to suspect that the better types of carpets sometimes labeled Uzbek have now been coopted into the Turkmen taxonomy. In this genre a great deal of useful grouping of carpets by structure, motifs, and color schemes has emerged. Linkage to the makers, however, seems to remain fuzzy. Anchor pieces are rare. Central Asia’s many political “national” jurisdictions are a Soviet invention (by the then commissar of nationalities)[8] and were imposed using other than clan and ethnicity criteria, resulting to some extent in masking the complex make-up of Central Asia’s many tribal confederations. A brief look at the evolving terminology with respect to provenance may be a helpful reminder that just who wove certain rugs in the current Uzbek and Turkmen oeuvre may be a mystery. It is Moshkova’s field work, not its general text, which is important. Sadykov’s attempt to the contrary notwithstanding it is doubtful that the making of pile carpets was of much significance in the crafts world of the latter 20th c., if ever. The Uzbek textiles for the most part were the product of the needle, not the comb.

[1]Kustarnye promysly v bytu narodov [daily life of the people] Uzbekistana XIX—XX vv , Avtorskii kollektiv: N. S. Sadykova, L. G. Lefteeva, N. K. Sultanova, K. Tursunaltsev, Tashkent, 1986, pp. 56—58. A Russian curator’s work was published in English at approximately the same time, a once over lightly review of all Central Asian types: Tzareva, Elena, Rugs and Carpets from Central Asia, 1984. There is no index or table of contents; text is minimal; illustrations are excellent; Uzbek materials appear in pp. 168 – 179. [2]Kovry Narodov Srednei Azii kontsa XIX – nachala XX vv, Tashkent, 1970. For Anglophones: Carpets of the People of Central Asia, ed. and trans. by George W. O’Bannon and Ovadan K. Amanova-Olsen, 1996. The relevant chapters are; Moshkova, V. G. and Morozova, A. S., “General Information on Weaving in Uzbekistan”, p. 76 ff.; Moshkova, V. G.,“Weaving of the Turkmen Uzbeks of the Nurata Basin”, p.107, ff.; Moshkova, V. G., “Kyrgyz Weaving in the Fergana Valley”, p. 129, ff.; Moshkova, V. G., “Arab Weaving of Kashkadarya Oblast”, p. 153 ff. The Moshkova book many years ago was somewhat off-handedly (and unfairly) dismissed by the chief textiles curator of the state museum in Prague as “warmed-over” Felkersham. [3] O’Bannon, op. cit., has included a useful note on this subject, p. 102. [4]This description seems to parallel that of a carpet fragment illustrated in Moshkova and attributed to Samarcand oblast’. Moshkova, V. G., op. cit., p.53. Which in turn appears in color on p. 56 in O’Bannon, op. cit. [5] Foelkersam, Baron A., Starye Gody, Starinnyie kovry Srednei Azii, June, 1915, p. 35 ff. [6]Kerki was the uppermost navigable site on the river; hence a water to land (or vice versa) transfer point. [7]Khanikov, Nikolai Vladimirovich, Bokhara: Its Amir and Its People, trans. de Bode, Baron Clement A., 1845, p. 81 [8] Stalin Ilmokli biziz – special stitch with hooks for chain-stitched embroideryterma – the name of a technique of palas-making, widespread in its use

Copyright � Richard E. Wright, All Rights Reserved |